1.2. Software Development Processes: Plan and Document¶

If builders built buildings the way programmers wrote programs, then the first woodpecker that came along would destroy civilization.

—Weinberg’s Second Law, 1978, attributed to Gerald Weinberg, University of Nebraska computer scientist

The general unpredictability of software development in the late 1960s, along with the software disasters similar to ACA, led to the study of how high-quality software could be developed on a predictable schedule and budget. Drawing the analogy to other engineering fields, the term software engineering was coined (Naur and Randell 1969). The goal was to discover methods to build software that were as predictable in quality, cost, and time as those used to build bridges in civil engineering.

One thrust of software engineering was to bring an engineering discipline to what was often unplanned software development. Before starting to code, come up with a plan for the project, including extensive, detailed documentation of all phases of that plan. Progress is then measured against the plan. Changes to the project must be reflected in the documentation and possibly to the plan.

The goal of all these “Plan-and-Document” software development processes is to improve predictability via extensive documentation, which must be changed whenever the goals change. Here is how textbook authors put it (Lethbridge and Laganiere 2002; Braude 2001):

Documentation should be written at all stages of development, and includes requirements, designs, user manuals, instructions for testers and project plans.

—Timothy Lethbridge and Robert Laganiere, 2002

Documentation is the lifeblood of software engineering.

—Eric Braude, 2001

This process is even embraced with an official standard of documentation: IEEE/ANSI stan- dard 830/1993.

Governments like that of the US have elaborate regulations to prevent corruption when acquiring new equipment, which lead to lengthy specifications and contracts. Since the goal of software engineering was to make software development as predictable as building bridges, including elaborate specifications, government contracts were a natural match to Plan-and- Document software development. Thus, like many countries, US acquisition regulations left the ACA developers little choice but to follow a Plan-and-Document lifecycle.

Of course, like other engineering fields, the government has escape clauses in the contracts that let it still acquire the product even if it is late. Ironically, the contractor makes more money the longer it takes to develop the software. Thus, the art is in negotiating the contract and the penalty clauses. As one commentator on ACA noted (Howard 2013), “The firms that typically get contracts are the firms that are good at getting contracts, not typically good at executing on them.” Another noted that the Plan-and-Document approach is not well suited to modern practices, especially when government contractors focus on maximizing profits (Chung 2013).

An early version of this Plan-and-Document software development process was devel- oped in 1970 (Royce 1970). It follows this sequence of phases:

Requirements analysis and specification

Architectural design

Implementation and Integration

Verification

Operation and Maintenance

Given that the earlier you find an error the cheaper it is to fix, the philosophy of this process is to complete a phase before going on to the next one, thereby removing as many errors as early as possible. Getting the early phases right could also prevent unnecessary work downstream. As this process could take years, the extensive documentation helps to ensure that important information is not lost if a person leaves the project and that new people can get up to speed quickly when they join the project.

Because it flows from the top down to completion, this process is called the Waterfall software development process or Waterfall software development lifecycle. Understandably, given the complexity of each stage in the Waterfall lifecycle, product releases are major events towardwhichengineersworkedfeverishlyandwhichareaccompaniedbymuchfanfare. In the Waterfall lifecycle, the long life of software is acknowledged by a maintenance phase that repairs errors as they are discovered. New versions of software developed in the Waterfall model go through the same several phases, and take typically between 6 and 18 months.

The Waterfall model can work well with well-specified tasks like NASA space flights, but it runs into trouble when customers change their minds about what they want. A Turing Award winner captures this observation:

Plan to throw one [implementation] away; you will, anyhow.

—Fred Brooks, Jr.

That is, it’s easier for customers to understand what they want once they see a prototype and for engineers to understand how to build it better once they’ve done it the first time.

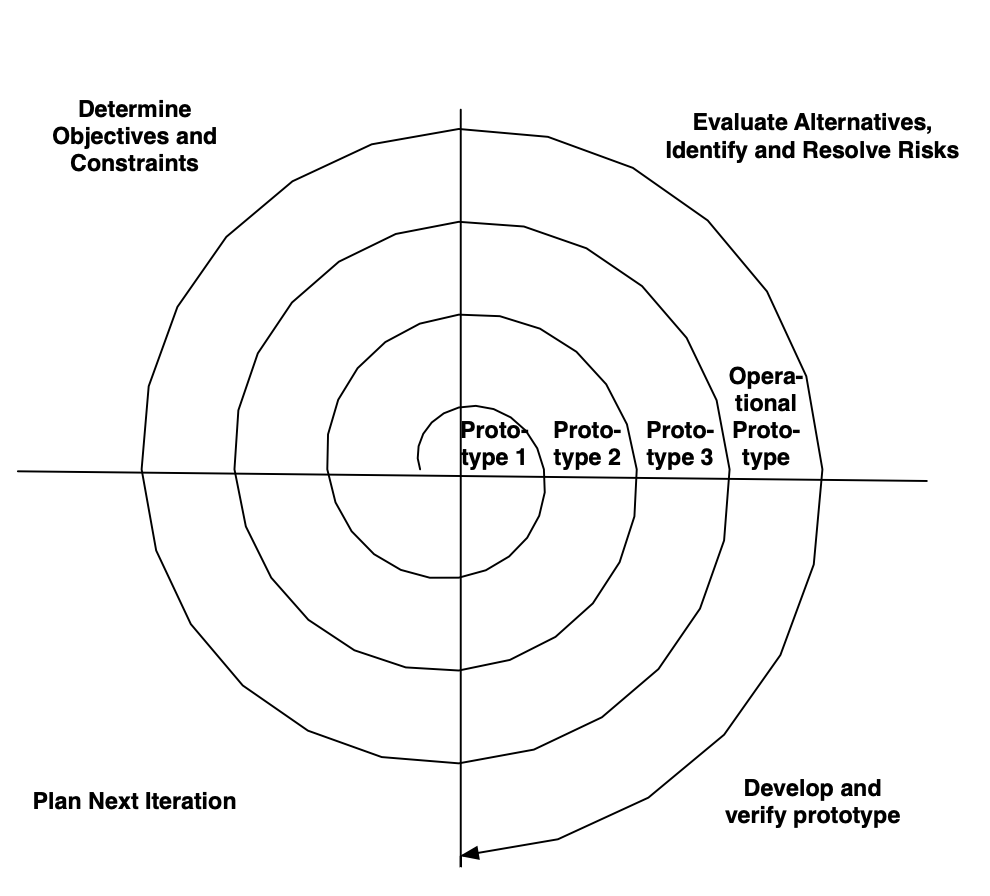

This observation led to a software development lifecycle developed in the 1980s that combines prototypes with the Waterfall model (Boehm 1986). The idea is to iterate through a sequence of four phases, with each iteration resulting in a prototype that is a refinement of the previous version. Figure 1.2 illustrates this model of development across the four phases, which gives this lifecycle its name: the Spiral model. The phases are:

Determine objectives and constraints of this iteration

Evaluate alternatives and identify and resolve risks

Develop and verify the prototype for this iteration

Plan the next iteration

Rather than document all the requirements at the beginning, as in the Waterfall model, the requirement documents are developed across the iteration as they are needed and evolve with the project. Iterations involve the customer before the product is completed, which reduces chances of misunderstandings. However, as originally envisioned, these iterations were 6 to 24 months long, so there is plenty of time for customers to change their minds during an iteration! Thus, Spiral still relies on planning and extensive documentation, but the plan is expected to evolve on each iteration.

Given the importance of software development, many variations of Plan-and-Document methodologies were proposed beyond these two. A recent one is called the Rational Unified Process (RUP) (Kruchten 2003), developed during the 1990s, which combines features of both Waterfall and Spiral lifecycles as well standards for diagrams and documentation. We’ll use RUP as a representative of the latest thinking in Plan-and-Document lifecycles. Unlike Waterfall and Spiral, it is more closely allied to business issues than to technical issues.

Like Waterfall and Spiral, RUP has phases:

Inception: makes the business case for the software and scopes the project to set the schedule and budget, which is used to judge progress and justify expenditures, and initial assessment of risks to schedule and budget.

Elaboration: works with stakeholders to identify use cases, designs a software archi- tecture, sets the development plan, and builds an initial prototype.

Construction: codes and tests the product, resulting in the first external release.

Transition:moves the product from development to production in the real environment, including customer acceptance testing and user training.

Unlike Waterfall, each phase involves iteration. For example, a project might have one inception phase iteration, two elaboration phase iterations, four construction phase iterations, and two transition phase iterations. Like Spiral, a project could also iterate across all four phases repeatedly.

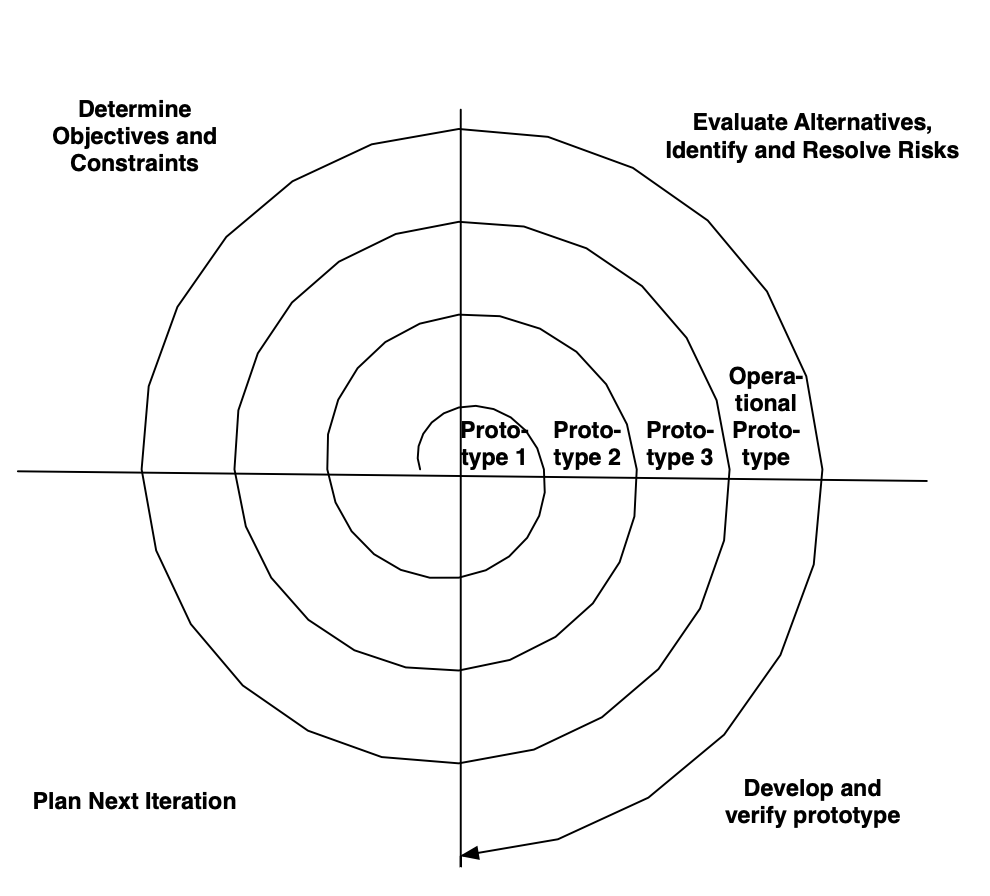

In addition to the dynamically changing phases of the project, RUP identifies six “engineering disciplines” (also known as workflows) that people working on the project should collectively cover:

Business Modeling

Requirements

Analysis and Design

Implementation

Test

Deployment

These disciplines are more static than the phases, in that they nominally exist over the whole lifetime of the project. However, some disciplines get used more in earlier phases (like business modeling), some periodically throughout the process (like test), and some more towards the end (deployment). Figure 1.3 shows the relationship of the phases and the disciplines, with the area indicating the amount of effort in each discipline over time.

An unfortunate downside to teaching a Plan-and-Document approach is that students may find software development tedious (Nawrocki et al. 2002; Estler et al. 2012). Of course, this is hardly a strong enough reason not to teach it; the good news is that there are alternatives that work just as well for many projects that are a better fit to the classroom, as we describe in the next section.

Self-Check 1.2.1. What are a major similarity and a major difference between processes like Spiral and RUP versus Waterfall?

All rely on planning and documentation, but Spiral and RUP use iteration and prototypes to improve them over time versus a single long path to the product.

Self-Check 1.2.2. What are the differences between the phases of these Plan-and-Document processes?

Waterfall phases separate planning (requirements and architectural design) from implemen- tation. Testing the product before release is next, followed by a separate operations phase. The Spiral phases are aimed at an iteration: set the goals for an iteration; explore alternatives; develop and verify the prototype for this iteration; and plan the next iteration. RUP phases are tied closer to business objectives: inception makes business case and sets schedule and budget; elaboration works with customers to build an initial prototype; construction builds and test the first version; and transition deploys the product.