3.5. RESTful APIs: Everything is a Resource¶

An API that isn’t comprehensible isn’t usable.

—James Gosling, inventor of Java

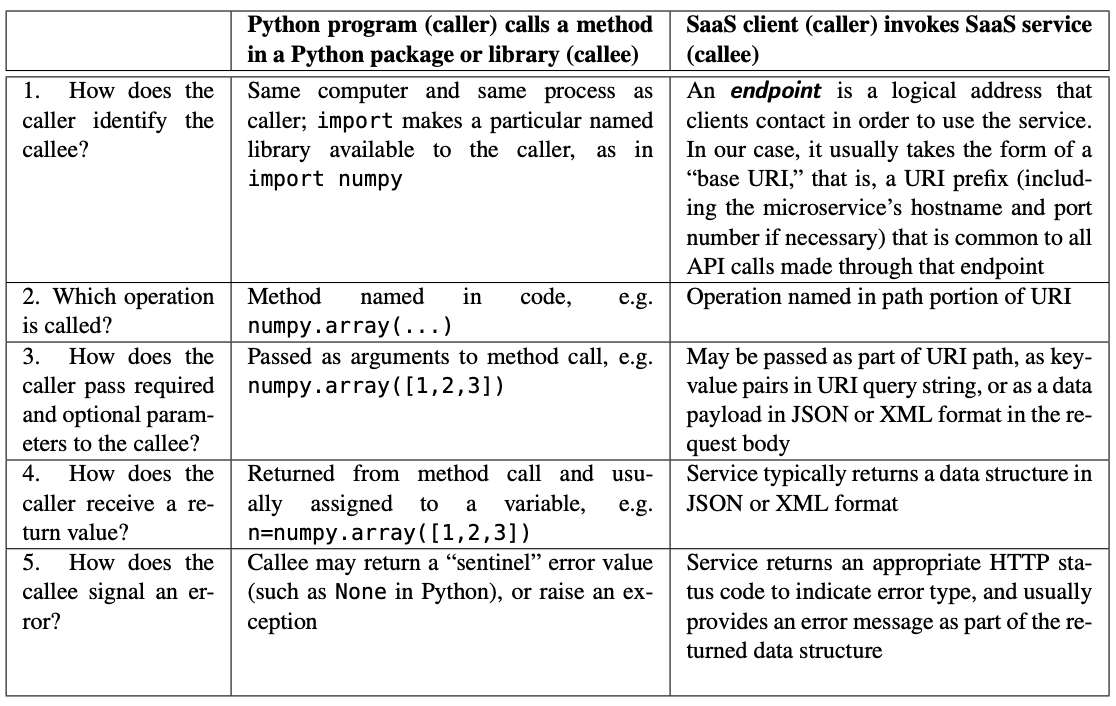

The premise of service-oriented architecture is that each service provides a well-defined set of operations on one or a few related types of resources—analogous to a library for a programming language. In other words, clients need a way to name the server function to be called, pass arguments to it, consume return values, detect and handle server exceptions (errors in execution), and so on, just as when an application calls a library function, but all subject to the constraints of using HTTP for communication. The term API, or Application Programming Interface, refers to the “contract” between a caller and callee, whether these are a program calling a library function or a SaaS client invoking a service on a SaaS server, as Figure 3.5 shows.

Unfortunately, rows 2 and 3 in the figure are problematic, because HTTP does not pre- scribe a way to “name a remote function” or “pass parameters” since those tasks were never part of its original design. In particular, the HTTP and URI specifications offer no conventions regarding the semantics (implied meaning) of how URIs are constructed or how these tasks should occur. There was early and widespread recognition that standardizing the con- ventions for such communication would enable the creation of an ecosystem in which any client, not just a Web browser, could make use of a given server in different ways.

In most of the microservices world, these conventions are articulated by REST, short for RE**presentational **S**tate **T**ransfer. In 2000, computer scientist Roy Fielding proposed REST in his Ph.D. dissertation as a way of mapping requests to actions that is particularly well suited to a service-oriented architecture. REST is not a standard, but a design stance regarding how a service should be constructed, and by extension, what its API should look like. Fielding’s idea was to represent the various entities manipulated by a Web app as **resources (hence representational), and to construct routes so that any HTTP request would contain all the information necessary to identify both a resource and the action to be performed on it, which might cause a change of state in one or more resources (hence state transfer). An API that adheres to Fielding’s guidelines is said to be RESTful, and the routes (HTTP method plus URI) defined by the API to invoke particular actions are said to be RESTful routes.

Although simple to explain, REST is an unexpectedly powerful principle for simplifying and organizing SaaS applications, because it makes the app designer think carefully about how each type of entity manipulated by the app can be represented as a resource, what operations can be done to that resource, and what conditions or assumptions must hold in order for a request for such an operation to be self-contained. For any RESTful API operation, it should be straightforward to answer the following questions:

What is the primary resource affected by the operation?

What is the operation to be done on that resource? What are the possible results? What are the possible side effects, if any?

What other data is necessary to complete the operation, if any, and how is it specified?

For example, consider the answers to the above questions in the case of posting a review for the movie “2001: A Space Odyssey,” a classic favorite of one of your authors:

The primary resource is the new review for the specific movie “2001: A Space Odyssey,” which might include (for example) a numerical rating and a few lines of text.

The operation is to create a new review using that information. One possible result is success, with the side effect that a new review is created. The other possible result is that creating the review fails for a variety of possible reasons (perhaps this client is not authorized to post reviews, or the database is full, or no more reviews are allowed for this movie), in which case there are no side effects.

Besides the review itself, the additional necessary data is some identification of which movie the review is intended to be linked to. As we will see, this identifier will likely be passed as part of the route, either as a component in the path portion of the URI or as a parameter in the query-string portion of the URI. Also, if the review app allows op- tionally associating a reviewer name or ID with the reviewer, an identifier representing the reviewer may similarly be necessary.

The API documentation should describe what operations are available and how the required and optional arguments should be provided for each operation. As we’ll learn in Chapter 4, Rails and other frameworks have built-in support for easily defining RESTful routes.

In its purest form, a RESTful API defines up to five operations on a resource, captured by the acronym CRUDI: Create a new instance of a resource, Read

(retrieve) a copy of a resource, Update (make changes to) a resource, Delete a resource, and list an Index of all available resources of a given type,

possibly filtered by particular criteria. Many APIs go further and define additional operations specific to the resource types used by that service.

Nearly always, each resource is given a unique ID—usually a number—that will serve as the “permanent handle” to that resource and is never reused even if

the resource is deleted. A common usage pattern for RESTful APIs is to return a list of resources (with their IDs) corresponding to a search operation; the

client can then retrieve the desired resources one by one via their IDs. Consistent with Section 3.2, RESTful routes whose actions have no side effects typically

use GET, while those with side effects use POST, PUT, or PATCH.

We can now describe concretely how RESTful service APIs address the requirements of rows 1–3 of Figure 3.5. (You’re strongly encouraged to consult the API documentation at https://developers.themoviedb.org/3 as you read the rest of thie section.) Recall Figure 3.2, which shows the various parts of a URI. RESTful APIs observe several conventions for how those parts of the URI are constructed when making an API call:

The hostname component of the URI tells us which server provides the service: https://api.themoviedb.org.

In addition, most servers providing RESTful APIs specify a base URI, or common URI prefix that should be prepended to all API calls. You can see from the figure that all of the URIs begin with https://api.themoviedb.org/3/; this base URI or hostname-plus-prefix is sometimes referred to as the API endpoint, or logical address that clients contact in order to use the service.

In this case, the API documentation tells us that the component 3 of the end- point name refers to the version number of the API. Making the version number part of the URI allows the API to evolve while preserving compatibility with older clients. You may also see variants such as https://themoviedb.org/api/v3/, https://api.themoviedb.org/v3/, and others.

The URI path components following the prefix specify the operation to be performed and the resource on which to perform it. API documentation frequently uses a colon (:) or curly braces to indicate a URI component corresponding to a resource ID, so the API documentation might state that the route

GET /movie/{movie_id}orGET /movie/ :movie_idrequests detailed information for the specific movie whose numeric ID is substituted for{movie_id}or:movie_idin the URI.

In the next section we describe exactly how the data associated with these requests is formatted and how errors are handled—rows 4 and 5 of the figure.

A common though not universal feature of RESTful APIs is that the structure of the URI path itself reveals information about the relationships among resource

types. For example, the TMDb API route GET /movie/{movie_id}/reviews, retrieves all the reviews for a particular movie—effectively, the Index operation on

reviews, constrained to a particular movie. The structure of the URI suggests that the same movie can have many associated reviews (a so-called “has-many” relationship,

which we’ll meet in Chapter 5). Similarly, a hypothetical route such as GET /movies/5/reviews/22, to request the content of review ID 22 associated with movie ID 5,

might seem redundant since the review ID must be unique anyway; but the route structure reveals an otherwise non-obvious relationship. Not all RESTful sites follow this

practice, though: the TMDb route for a particular review is simply GET /reviews/ {review_id}, and some TMDb routes use multiple path components (terms separated by slashes)

to express different sub-operations on a resource rather than relationships among resource types.

You can verify by reading the TMDb API docs that the call for retrieving all reviews for a movie actually returns some of the content of each review. In a “purer” RESTful API, such an Index call might just return a list of review IDs, and the client could then retrieve the contents of individual reviews by their review ID. It’s possible that the TMDb API sought to make things more efficient so that enough information is returned for each review that the client could decide which reviews were worth getting more details on. But if a movie had thousands of reviews, returning review data rather than just review IDs for all those reviews might become unwieldy.

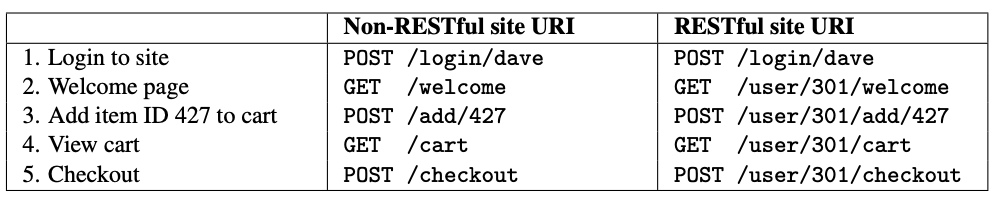

RESTfulness may seem an obvious design choice, but until Fielding crisply character- ized the REST philosophy and began promulgating it, many Web apps were designed non-RESTfully. Figure 3.6 shows how a hypothetical non-RESTful e-commerce site might im- plement the functionality of allowing a user to login, adding a specific item to his shopping cart, and proceeding to checkout. For the hypothetical non-RESTful site, every request after the login (line 3) relies on implicit information: line 4 assumes the site “remembers” who the currently-logged-in user is to show them the welcome page, and line 7 assumes the site “remembers” who has been adding items to their cart for checkout. In contrast, each URI for the RESTful site contains enough information to satisfy the request without relying on such implicit information: after Dave logs in, the fact that his user ID is 301 is present in every request, and his cart is identified explicitly by his user ID rather than implicitly based on the notion of a currently-logged-in user.

Self-Check 3.5.1. Which of these routes for updating the information of movie ID 35 follow good HTTP and REST practices: (a) POST /movie/35 , (b) POST /movies/35 ,

(c) PUT / movies/35 , (d) PUT /movies/35 , (e) GET /movies/35 , (f) GET /movies/35.

All except (e) and (f) follow defensible practices. Whether to use singular or plural is a matter of style and convention, but

GETshould not be used for routes whose actions have side effects