3.4. From Web Sites to Microservices: Service-Oriented Architecture¶

Nobody should start to undertake a large project. You start with a small trivial project, and you should never expect it to get large. If you do, you’ll just overdesign and generally think it is more important than it likely is at that stage. Or worse, you might be scared away by the sheer size of the work you envision. So start small, and think about the details. Don’t think about some big picture and fancy design. If it doesn’t solve some fairly immediate need, it’s almost certainly over-designed. And don’t expect people to jump in and help you. That’s not how these things work. You need to get something half- way useful first, and then others will say “hey, that almost works for me,” and they’ll get involved in the project.

—Linus Torvalds, interviewed2 by Preston St. Pierre in Linux Times, Oct 25, 2004.

When the Web began in 1990, HTTP servers existed primarily to serve static content (originally the text and images of scientific papers) that browsers would display. Each time the browser made another HTTP request, the server would deliver a new web page for the browser to show. But the emergence of SaaS around 1995 soon shifted the functionality of servers: rather than simply returning copies of static Web pages, servers would now run a program, and create HTML pages “on the fly” that implemented that program’s user interface. However, it was still the case that every new HTTP request resulted in the browser loading and displaying a new page. The next evolutionary step was the appearance of AJAX, or Asynchronous JavaScript And XML. If a browser supported AJAX, pages could include code written in the JavaScript language, and that code could make subsequent HTTP requests to the server without causing a page reload. In response to those requests, the server would return not an HTML page, but a data structure in either XML or JSON format, both of which we’ll meet shortly. The JavaScript code running in the browser would use that data to determine how to change the appearance or behavior of the displayed page, all without causing a page reload.

AJAX marked a turning point in the relationship between a Web site and a client: instead of receiving HTML pages and functioning primarily as a display engine, the client was es- sentially calling a function on the remote server and expecting to get some data back, just as if the client was calling a library function. This shift in perspective invited a new way of looking at the Web: as a set of independent services that could be composed to produce larger sites—a so-called Service Oriented Architecture (SOA).

SOA had long suffered from lack of clarity and direction…. SOA could in fact die—not due to a lack of substance or potential, but simply due to a seemingly endless proliferation of misinformation and confusion.

—Thomas Erl, About the SOA Manifesto, 2010

SOA as an architectural pattern may have been a new perspective on structuring the Web, but it was certainly not a new idea. Despite initial skepticism about whether SOA was more than just a marketing “buzzword,” one very prominent company was internally (and, at the time, silently) making SOA quite concrete. The e-commerce giant Amazon.com launched its retail site in 1995 powere by a monolithic application — a single large application that handled all aspects of the site. According to the blog of former Amazonian Steve Yegge, in 2002 the CEO and founder of Amazon mandated a change to what we would today call SOA. Yegge claims that Jeff Bezos broadcast an email to all employees along the following lines (we are paraphrasing the main points of Yegge’s description for conciseness):

All teams responsible for different subsystems of Amazon.com will henceforth expose their subsystem’s data and functionality through service interfaces only. No subsystem is to be allowed direct access to the data “owned” by another subsystem; the only access will be through an interface that exposes spe- cific operations on the data. Furthermore, every such interface must be designed so that someday it can be exposed to outside developers, not just used within Amazon.com itself.

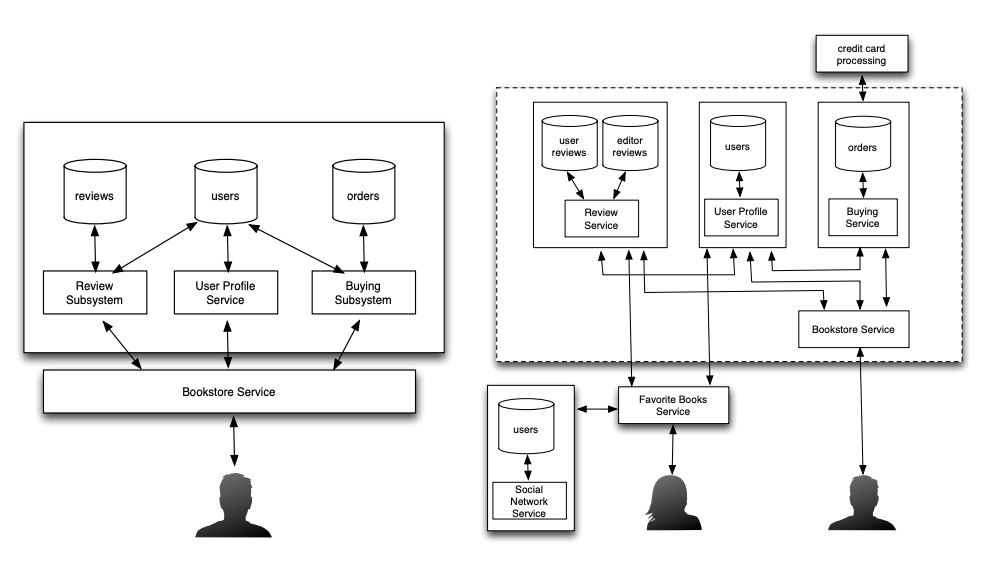

In this decree, Bezos captures the critical distinction of SOA: the only way one service can name or access another service’s data is to request specific operations on that data through an external interface that provides those operations. As an example, suppose we wanted to create a simple bookstore service where users can post reviews of books they’ve bought and maintain a profile of their reading interests. We’d need three subsystems: book reviews, user profiles, and buying. The left side of Figure 3.3 shows the silo version, similar to how Amazon.com worked in 1995. Each subsystem can internally share access to data directly in different subsystems. For example, the reviews subsystem can get user profile info out of the users subsystem. The only externally visible interface is “the bookstore.”

The right side of Figure 3.3 shows the SOA version of the bookstore service, in which all subsystems are separate and independent. Even though all are inside the “boundary” of the bookstore, which is shown as a dotted rectangle, the subsystems interact with each other as if they were separate. For example, if the reviews subsystem wants to update a user’s profile to indicate that the user has written a review, the reviews subsystem can’t reach directly into the users database. Instead, it has to ask the users service to update the user’s information, via whatever interface is provided for that purpose. If no such operation is provided, the reviews team must negotiate with the user database team to get them to expose the necessary operation.

Of course, you as an independent web developer cannot access Amazon’s User Profile service to manage users profiles for your own e-commerce site; it’s for Amazon’s internal use only. A microservice, in contrast, is a standalone service that performs just one type of task, and is specifically designed to be accessible from and incorporated into the functionality of any other outside service (perhaps for a fee). Though there is no hard-and-fast criterion distinguishing the scope of a microservice from that of a service, the prefix micro is intended to promote an “extreme SOA” design stance in which each microservice is responsible for a single narrowly-defined function. For example, Google Maps feels like a single app when you use it in a browser, but the different “clusters” of related functionality used by that app — drawing the map, computing driving directions, geocoding addresses, and so on—appear as distinct microservices to the underlying JavaScript code that implements the app. A rough rule of thumb is that the scope of a microservice should correspond to a set of closely related operations on a very tightly integrated set of resources. Notwithstanding, since there is no hard distinction between a service and a microservice, we will use the term service throughout. We will adopt the following rough definition, found in Nadareishvili et al. 2016: “A (micro)service is an independently deployable component of bounded scope that supports interoperability though message-based communication.” Based on this definition, we can see that the monolithic bookstore fails to be “micro” not just because of its size, but because its components are not independently deployable since they share access to databases.

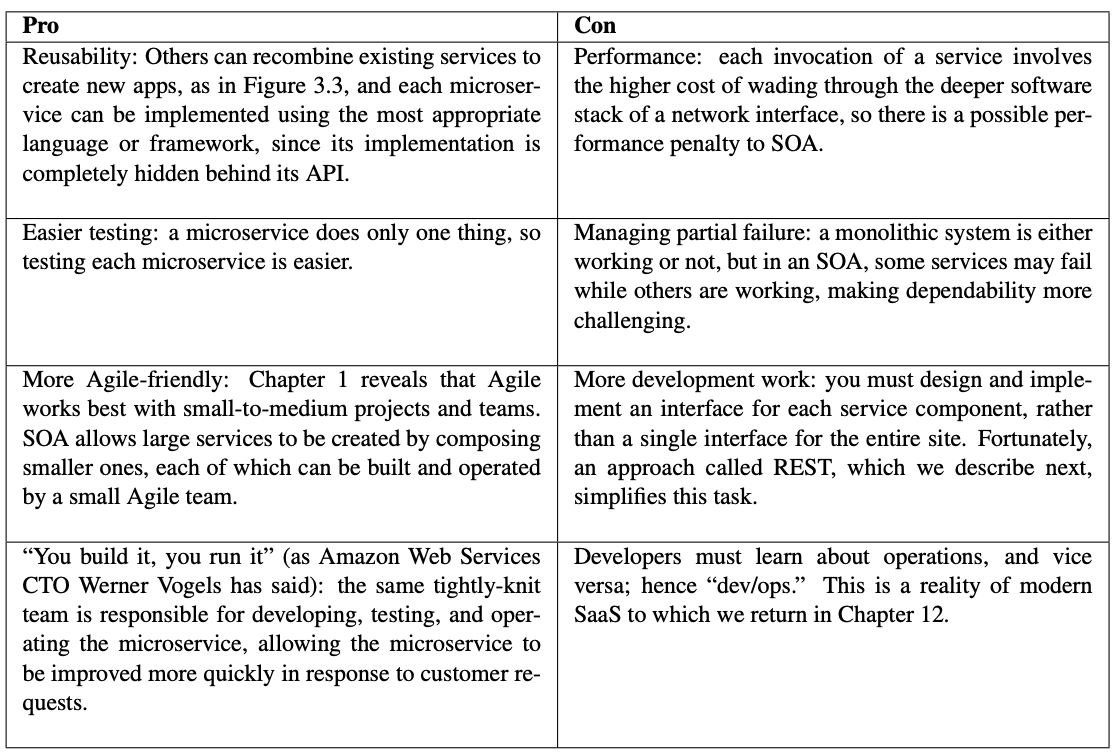

As Figure 3.4 shows, there are both pros and cons to preferring a service-oriented archi- tecture over a monolithic one. In short, we can think of microservices as a manifestation of extreme programming (XP) as applied to service-oriented architecture: If it’s good for services to be independently evolvable, make each one as compact as possible to maximize that independence. Microservices may also arise by design or by splitting up an existing large service, as occurred with Twitter. Around 2013, their monolithic Rails application, which they humorously called “the MonoRail” internally, was split up into a large number of microservices, most written in Java, Scala, or Clojure.

Self-Check 3.4.1. Another take on SOA is that it is just a common sense approach to improving programmer productivity. Which productivity mechanism does SOA best exemplify: Clarity via conciseness, Synthesis, Reuse, or Automation and Tools?

Reuse! The purpose of making internal interfaces visible is so that programmers can stand on the shoulders of others.