8.10. The Plan-And-Document Perspective on Testing¶

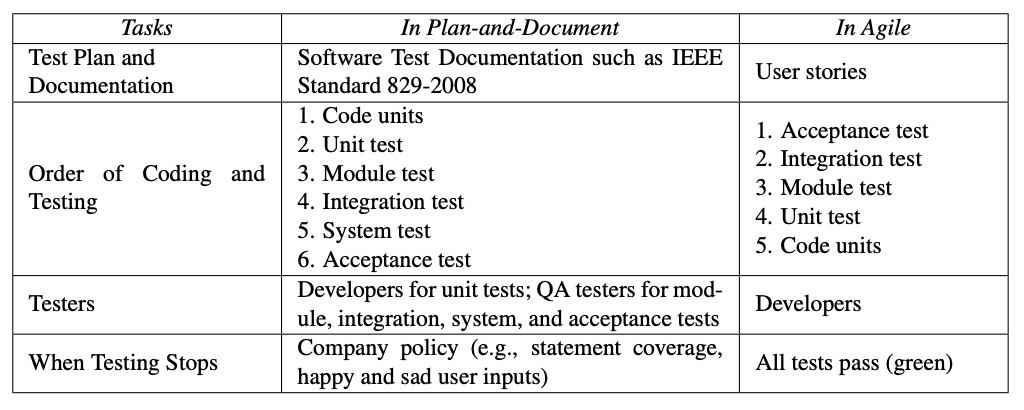

The project manager takes the Software Requirements Specification from the requirements planning phase and divides it into the individual program units. Developers then write the code for each unit, and then perform unit tests to make sure they work. In many organizations, quality assurance staff performs the rest of the higher-level tests, such as module, integration, system, and acceptance tests.

There are three options on how to integrate the units and perform integration tests:

Top-down integration starts with the top of tree structure showing the dependency among all the units. The advantage of top-down is that you quickly get some of the high level functions working, such as the user interface, which allows stakeholders to offer feedback for the app in time to make changes. The downside is that you have to create many stubs to get the app to limp along in this nascent form.

Bottom-up integration starts at the bottom of the dependency tree and works up. There is no need for stubs, as you can integrate all the pieces you need for a module. Alas, you don’t get an idea how the app will look until you get all the code written and integrated.

Sandwich integration, not surprisingly, tries to get the best of both worlds by integrat- ing from both ends simultaneously. Thus, you try to reduce the number of stubs by selectively integrating some units bottom-up and try to get the user interface opera- tional sooner by selectively integrating some units top-down.

The next step for the QA testers after integration tests is the system test, as the full app should work. This is the last step before showing it to customers for them to try out. Note that system tests cover both non-functional requirements, such as performance, and functional requirements of features found in the SRS.

One question for plan-and-document is how to decide when testing is complete. Typically, an organization will enforce a standard level of testing coverage before a product is ready for the customer. Examples might be statement coverage (all statements executed at least once), or all user input opportunities are tested with both good input and problematic input.

In the plan and document process, the final test is for the customers to try the product in their environment to decide whether they will accept the product or not. That is, the aim is validation, not just verification. In Agile development, the customer is involved in trying prototypes of the app early in the process, so there is no separate system test before running the acceptance tests.

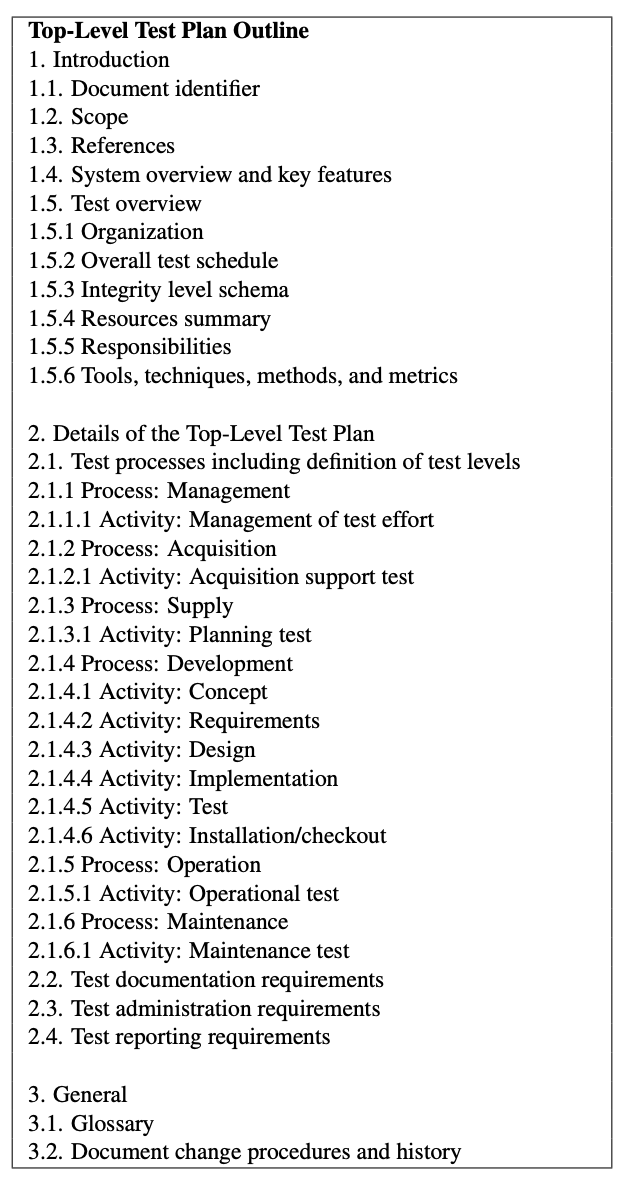

As you should expect from the plan-and-document process, documentation plays an important role in testing. Figure 8.14 gives an outline for a test plan based on IEEE Standard 829-2008.

While testing is fundamental to software engineering, quoting another Turing Award winner:

Program testing can be used to show the presence of bugs, but never to show their ab- sence!

—Edsger W. Dijkstra

Thus, there has been a great deal of research investigating approaches to verification beyond testing. Collectively, these techniques are known as formal methods. The general strategy is to start with a formal specification and prove that the behavior of the code follows the behavior of that spec. These are mathematical proofs, either done by a person or done by a computer. The two options are automatic theorem proving or model checking. Theorem proving uses a set of inference rules and a set of logical axioms to produce proofs from scratch. Model checking verifies selected properties by exhaustive search of all possible states that a system could enter during execution.

Because formal methods are so computationally intensive, they tend to be used only when the cost to repair errors is very high, the features are very hard to test, and the item being verified is not too large. Examples include vital parts of hardware like network protocols or safety critical software systems like medical equipment. For formal methods to actually work, the size of the design must be limited: the largest formally verified software to date is an operating system kernel that is less than 10,000 lines of code, and its verification cost about $500 per line of code (Klein et al. 2010).

Hence, formal methods are not good matches to high-function software that changes frequently, as is generally the case for Software as a Service.

Self-Check 8.10.1. Compare and contrast integration strategies including top-down, bottom-up, and sandwich integration.

Top-down needs stubs to perform the tests, but it lets stakeholders get a feeling for how the app works. Bottom-up does not need stubs, but needs potentially everything written before stakeholders see it work. Sandwich integration works from both ends to try to get both benefits.