1.3. Software Development Processes: The Agile Manifesto¶

If a problem has no solution, it may not be a problem, but a fact—not to be solved, but to be coped with over time.

—Shimon Peres

While plan-and-development processes brought discipline to software development, there were still software projects that failed so disastrously that they live in infamy. Programmers have heard these sorry stories of the Ariane 5 rocket explosion, the Therac-25 lethal radiation overdose, Mars Climate Orbiter disintegration, and the FBI Virtual Case File project abandonment so frequently that they are clichés. No software engineer would want these projects on their résumés.

One article even listed a “Software Wall of Shame” with dozens of highly-visible software projects that collectively were responsible for losses of $17B, with the majority of these projects abandoned (Charette 2005).

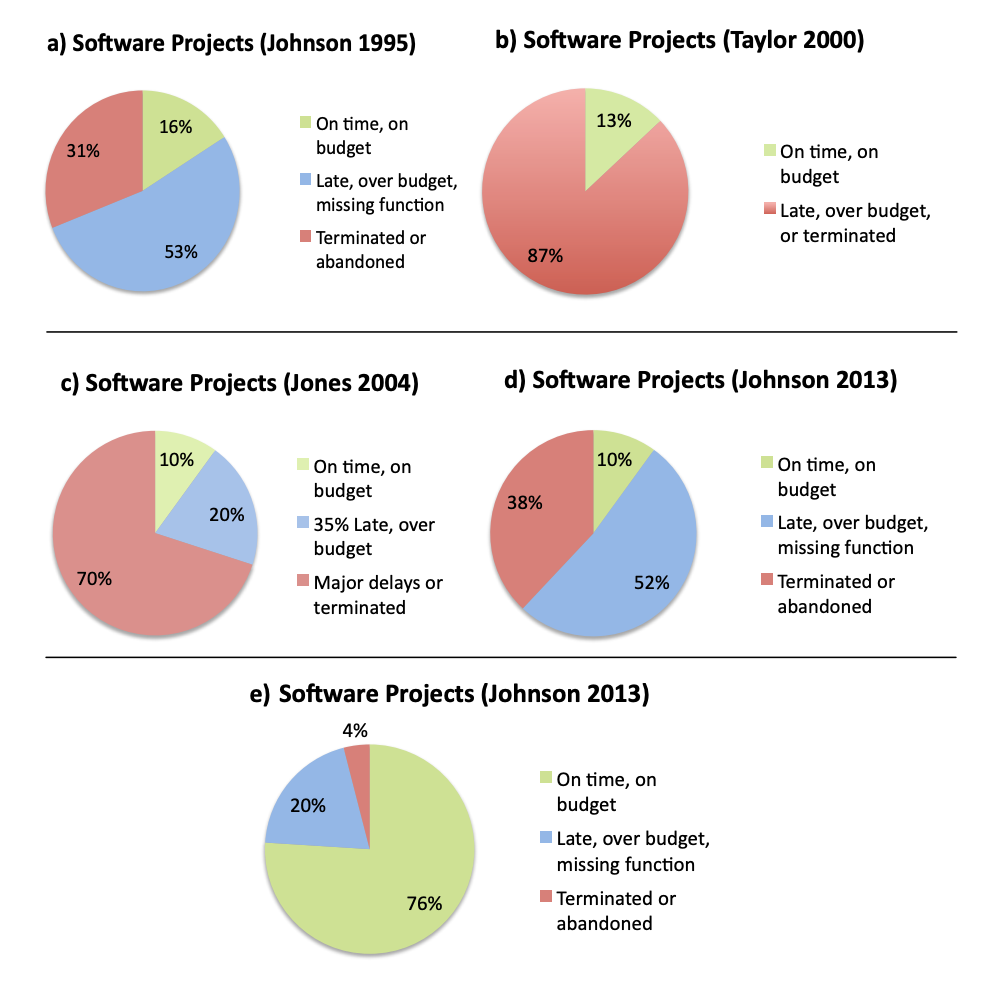

Figure 1.4 summarizes four surveys of software projects. With just 10% to 16% on time and on budget, more projects were cancelled or abandoned than met their mark. A closer look at the 13% of projects in survey (b) that were successful is even more sobering, as fewer than 1% of new development projects met their schedules and budgets. Although the first three surveys are 10 to 25 years old, survey d) is from 2013. Nearly 40% of these large projects were cancelled or abandoned, and 50% were late, over budget, and missing functionality. Using history as our guide, poor President Obama had only a one in ten chance that HealthCare.gov would have a successful debut.

Perhaps the “Reformation moment” for software engineering was the Agile Manifesto in February 2001. A group of software developers met to develop a lighter-weight software lifecycle. Here is exactly what the Agile Alliance nailed to the door of the “Church of Plan and Document”:

“We are uncovering better ways of developing software by doing it and helping others do it. Through this work we have come to value:

Individuals and interactions over processes and tools

Working software over comprehensive documentation

Customer collaboration over contract negotiation

Responding to change over following a plan

That is, while there is value in the items on the right, we value the items on the left more.”

This alternative development model is based on embracing change as a fact of life: developers should continuously refine a working but incomplete prototype until the customer is happy with the result, with the customer offering feedback on each iteration. Agile emphasizes test-driven development (TDD) to reduce mistakes by writing the tests before writing the code, user stories to reach agreement and validate customer requirements, and velocity to measure project progress. We’ll cover these topics in detail in later chapters.

Regarding software lifetimes, the Agile software lifecycle is so quick that new versions are available every week or two—with some even releasing every day—so they are not even special events as in the Plan-and-Document models. The assumption is one of basically continuous improvement over its lifetime.

We mentioned in the prior section that newcomers can find Plan-and-Document processes tedious, but this is not the case for Agile. This perspective is captured by a software engi- neering instructor’s early review of Agile:

Remember when programming was fun? Is this how you got interested in computers in the first place and later in computer science? Is this why many of our majors enter the discipline—because they like to program computers? Well, there may be promising and respectable software development methodologies that are perfectly suited to these kinds of folks…. [Agile] is fun and effective, because not only do we not bog down the process in mountains of documentation, but also because developers work face-to-face with clients throughout the development process and produce working software early on.

—Renee McCauley, “Agile Development Methods Poised to Upset Status Quo,” SIGCSE Bulletin, 2001

By de-emphasizing planning, documentation, and contractually binding specifications, the Agile Manifesto ran counter to conventional wisdom of the software engineering intelli- gentsia, so it was not universally welcomed with open arms (Cormick 2001):

[The Agile Manifesto] is yet another attempt to undermine the discipline of software en- gineering… In the software engineering profession, there are engineers and there are hackers… It seems to me that this is nothing more than an attempt to legitimize hacker behavior… The software engineering profession will change for the better only when cus- tomers refuse to pay for software that doesn’t do what they contracted for… Changing the culture from one that encourages the hacker mentality to one that is based on predictable software engineering practices will only help transform software engineering into a re- spected engineering discipline.

—Steven Ratkin, “Manifesto Elicits Cynicism,” IEEE Computer, 2001

One pair of critics even published the case against Agile as a 432-page book! (Stephens and Rosenberg 2003)

“The battle lines are drawn. Hostilities have broken out between armed camps of the software development community. This time the rallying cry is, “XP!” … What XP un- covered (again) is an ancient, sociological San Andreas fault that runs under the software community–programming versus software engineering (a.k.a. the scruffy hackers versus the tweedy computer scientists).”

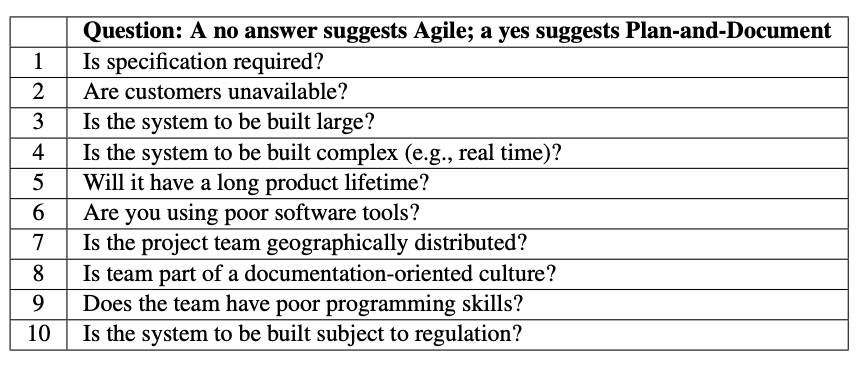

The software engineering research community went on to compare Plan-and-Document lifecycles to the Agile lifecycle in the field and found—to the surprise of some cynics— that Agile could indeed work well, depending on the circumstances. Figure 1.5 shows 10 questions from a popular software engineering textbook (Sommerville 2010) whose answers suggest when to use Agile and when to use Plan-and-Document methods.

While Figure 1.4(d) shows the disappointing results for large software projects, which do not use Agile, Figure 1.4(e) shows the success of small software projects—defined as costing less than $1M—that typically do use Agile. With three-fourths of these projects on time, on budget, and with full functionality, the results are in stark contrast to the other charts in the figure. Success has fanned Agile’s popularity, and recent surveys peg Agile as the primary development method for 60% to 80% of all programming teams in 2013 (ET Bureau 2012, Project Management Institute 2012). One paper even found Agile was used by the majority of programming teams that are geographically distributed, which is much more difficult to pull off (Estler et al. 2012).

Thus, we concentrate on Agile in the six software development chapters in Part II of the book, but each chapter also gives the perspective of the Plan-and-Document methodologies on topics like requirements, testing, project management, and maintenance. This contrast allows readers to decide for themselves when each methodology is appropriate. Part I introduces SaaS and SaaS programming environments, including Ruby, Rails, and Javascript.

Agile is a family of methodologies, not a single methodology. We follow Extreme Programming (XP), which includes one- to two-week iterations, behavior driven design (see Chapter 7), test-driven development (see Chapter 8), and pair programming (Section 2.2). Another popular variant is Scrum (Section 10.1), where self-organizing teams use two- to four-week iterations called sprints, and then regroup to plan the next sprint. A key feature of many Agile methodologies is a daily standup meeting to identify and overcome obstacles. While there are multiple roles in the scrum team, the norm is to rotate the roles over time. The Kanban approach is derived from Toyota’s just-in-time manufacturing process, which in this case treats software development as a pipeline. Here the team members have fixed roles, and the goal is to balance the number of team members so that there are no bottlenecks with tasks stacking up waiting for processing. One common feature is a wall of cards to illustrate the state of all tasks in the pipeline. There are also hybrid lifecycles that try to combine the best of two worlds. For example, ScrumBan uses the daily meetings and sprints of Scrum but replaces the planning phase with the more dynamic pipeline control of the wall of cards from Kanban.

While we now see how to build some software successfully, not all projects are small. We next show how to design software to enable composing smaller pieces into large services like Amazon.com.

Self-Check 1.3.1. True or False: A big difference between Spiral and Agile development is building prototypes and interacting with customers during the process.

False: Both build working but incomplete prototypes that the customer helps evaluate. The difference is that customers are involved every two weeks in Agile versus up to two years in with Spiral.

Self-Check 1.3.2. True or False: A big difference between Waterfall and Agile development is that Agile does not use requirements.

False: While Agile does not develop extensive requirements documents as does Waterfall, the interactions with customers lead to the creation of requirements as user stories, as we shall see in Chapter 7.