9.7. The Plan-And-Document Perspective on Working With Legacy Code¶

One reason for the term lifecycle from Chapter 1 is that a software product enters a maintenance phase after development completes. Roughly two-thirds of the costs are in maintenance versus one-third in development. One reason that companies charge roughly 10% of the price of software for annual maintenance is to pay the team that does the maintenance.

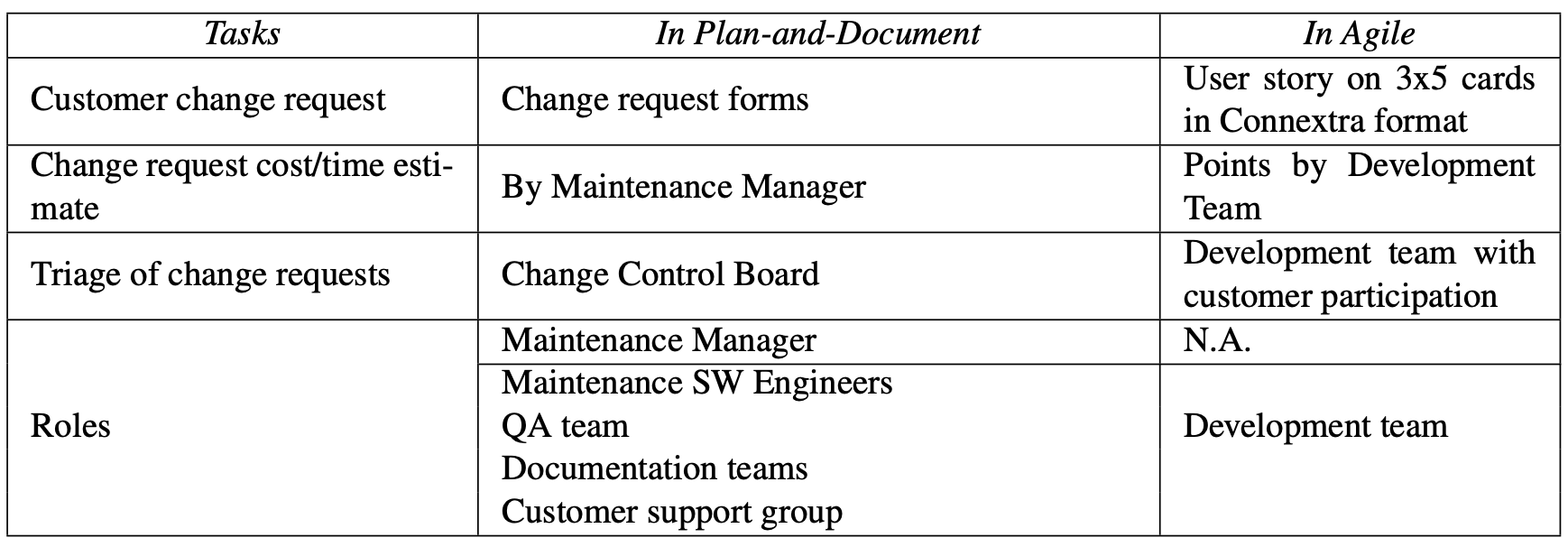

Organizations following Plan-And-Document processes typically have different teams for development and maintenance, with developers being redistributed onto new projects once the project is released. Thus, we now have a maintenance manager who takes over the roles of the project manager during development, and we have maintenance software engineers working on the team that make the changes to the code. Sadly, maintenance engineering has an unglamorous reputation, so it is typically performed by either the newest or least accomplished managers and engineers in an organization. Many organizations use different people for Quality Assessment to do the testing and for user documentation.

For software products developed using Plan-And-Document processes, the environment for maintenance is very different from the environment for development:

Working software—A working software product is in the field during this whole phase, and new releases must not interfere with existing features.

Customer collaboration—Rather than trying to meet a specification that is part of a negotiated contract, the goal for this phase is to work with customers to improve the product for the next release.

Responding to change—Based on use of the product, customers send a stream of change requests, which can be new features as well as bug fixes. One challenge of the maintenance phase is prioritizing whether to implement a change request and in which release should it appear.

Regression testing plays a much bigger role in maintenance to avoid breaking old features when developing new ones. Refactoring also plays a much bigger role, as you may need to refactor to implement a change request or simply to make the code more maintainable. There is less incentive for the extra cost and time to make the product easier to maintain in Plan-And-Document processes initially if the company developing the software is not the one that maintains it, which is one reason refactoring plays a smaller role during development.

As mentioned above, change management is based on change requests made by customers and other stakeholders to fix bugs or to improve functionality (see Section 10.7). They typically fill out change request forms, which are tracked using a ticket tracking system so that each request is responded to and resolved. A key tool for change management is a version control system, which tracks all modifications to all objects, as we describe in Sections 10.3 and 10.2.

The prior paragraphs should sound familiar, for we are describing Agile development; in fact, the three bullets are copied from the Agile Manifesto (see Section 1.3). Thus, maintenance is essentially an Agile process. Change requests are like user stories; the triaging of change requests is similar to the assignment of points and using Pivotal Tracker to decide how to prioritize stories; and new releases of the software product act as Agile iterations of the working prototype. Plan-and-document maintenance even follows the same strategy of breaking a large change request into many smaller ones to make them easier to assess and implement, just as we do with user stories assigned more than eight points (see Section 7.4). Hence, if the same team is developing and maintaining the software, nothing changes after the first release of the product when using the Agile lifecycle.

Although one paper reports successfully using an Agile process to maintain software developed using Plan-And-Document processes (Poole and Huisman 2001), normally an organization that follows Plan-And-Document for development also follows it for maintenance. As we saw in earlier chapters, this process expects a strong project manager who makes the cost estimate, develops the schedule, reduces risks to the project, and formulates a careful plan for all the pieces of the project. This plan is reflected in many documents, which we saw in Figures 7.6 and 8.14 and will see in the next chapter in Figures 10.11, 10.12, and 10.13. Thus, the impact of change in Plan-And-Document processes is not just the cost to change the code, but also to change the documentation and testing plan. Given the many more objects of Plan-And-Document, it takes more effort to synchronize to keep them all consistent when a change is made.

A change control board examines all significant requests to decide if the changes should be included in the next version of the system. This group needs estimates of the cost of a change to decide whether or not to approve the change request. The maintenance manager must estimate the effort and time to implement each change, much as the project manager did for the project initially (see Section 7.9). The group also asks the QA team for the cost of testing, including running all the regression tests and developing new ones (if needed) for a change. The documentation group also estimates the cost to change the documentation. Finally, the customer support group checks whether there is a workaround to decide if the change is urgent or not. Besides cost, the group considers the increased value of the product after the change when deciding what to do.

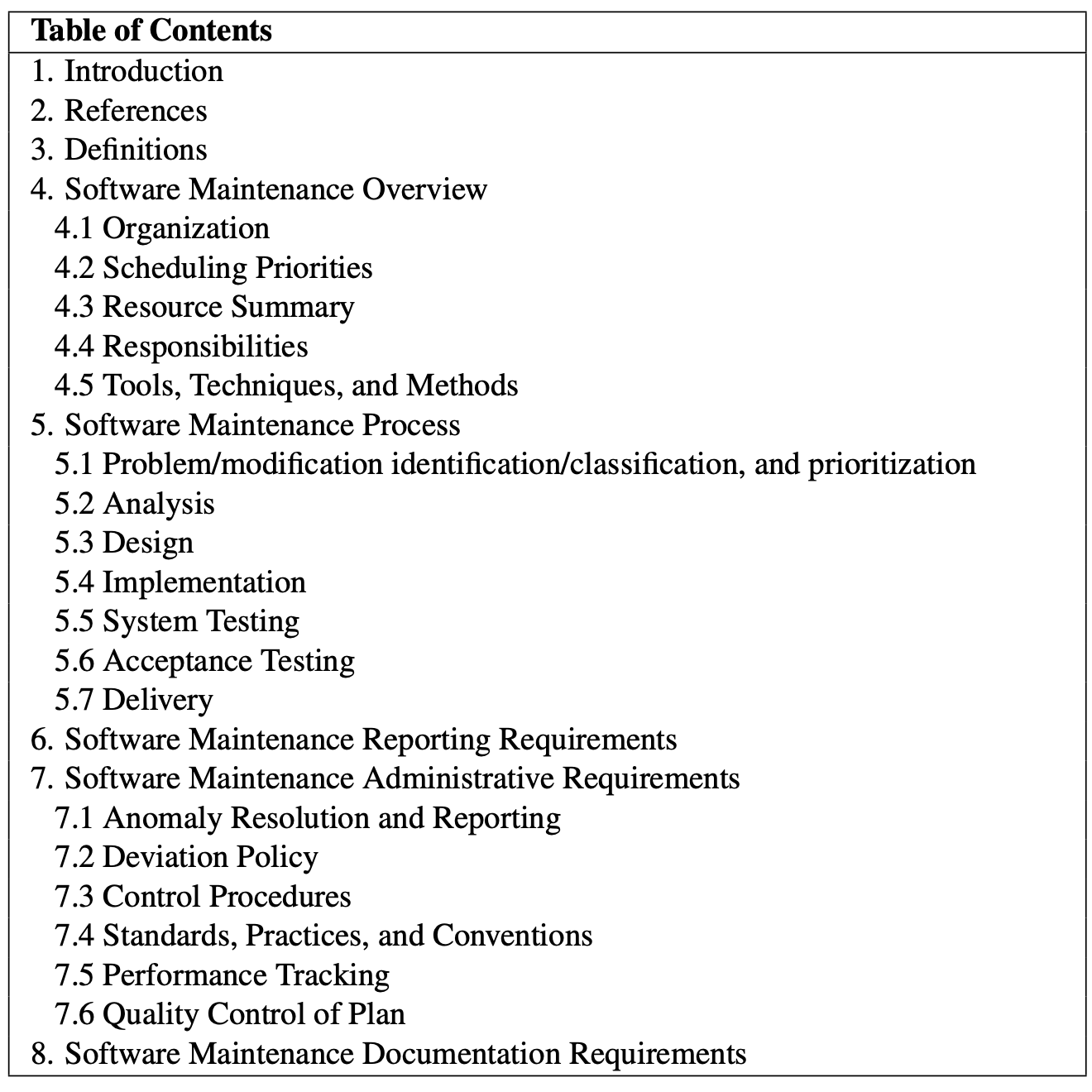

To help keep track what must be done in Plan-And-Document processes, you will not be surprised to learn that IEEE offers standards to help. Figure 9.21 shows the outline of a maintenance plan from the IEEE Maintenance Standard 1219-1998.

Ideally, changes can all be scheduled to keep the code, documents, and plans all in synchronization with an upcoming release. Alas, some changes are so urgent that everything else is dropped to try to get the new version to the customer as fast as possible. For example:

The software product crashes.

A security hole has been identified that makes the data collected by the product particularly vulnerable.

New releases of the underlying operating system or libraries force changes to the product for it to continue to function.

A competitor brings out product or feature that if not matched will dramatically affect the business of the customer.

New laws are passed that affect the product.

While the assumption is that the team will update the documentation and plans as soon as the emergency is over, in practice emergencies can be so frequent that the maintenance team can’t keep everything in synch. Such a buildup is called a technical debt. Such procrastination can lead to code that is increasingly difficult to maintain, which in turn leads to an increasing need to refactor the code as the code’s “viscosity” makes it more and more difficult to add functionality cleanly. While refactoring is a natural part of Agile, it less likely for the Change Control Committee to approve changes that require refactoring, as these changes are much more expensive. That is–as the name is intended to indicate–if you don’t repay your technical debt, it grows: the “uglier” the code gets, the more error-prone and time-consuming it is to refactor!

In addition to estimating the cost of each potential change for the Change Control Board, an organization’s management may ask what will be the annual cost of maintenance of a project. The maintenance manager may base this estimate on software metrics, just as the project manager may use metrics to estimate the cost to develop a project (see Section 7.9). The metrics are different for maintenance, as they are measuring the maintenance process. Examples of metrics that may indicate increased difficulty of maintenance include the average time to analyze or implement a change request and increases in the number of change requests made or approved.

At some point in the lifecycle of a software product, the question arises whether it is time for it to be replaced. An alternative that is related to refactoring is called reengineering. Like refactoring, the idea is to keep functionality the same but to make the code much easier to maintain. Examples include:

Changing the database schema.

Using a reverse engineering tool to improve documentation.

Using a structural analysis tool to identify and simplify complex control structures.

Using a language translation tool to change code from a procedure-oriented language like C or COBOL to an object-oriented language like C++ or Java.

The hope is that reengineering will be much less expensive and much more likely to succeed than reimplementing the software product from scratch.

Self-Check 9.7.1. True or False: The cost of maintenance usually exceeds the cost of development.

True

Self-Check 9.7.2. True or False: Refactoring and reengineering are synonyms.

False: While related terms, reengineering often relies on automatic tools and occurs as software ages and maintainability becomes more difficult, yet refactoring is a continuous process of code improvement that happens during both development and maintenance.

Self-Check 9.7.3. Match the Plan-and-Document maintenance terms on the left to the Agile terms on the right:

Change request |

Iteration |

Change request cost estimate |

Icebox, Active columns in Pivotal Tracker |

Change request triage |

Points |

Release |

User story |

Change request ⇐⇒ User story; Change request cost estimate ⇐⇒ Points; Release ⇐⇒ Iteration; and Change request triage ⇐⇒ Icebox, Active columns in Pivotal Tracker.