7.1. Behavior-Driven Design and User Stories¶

Behavior-Driven Design is Test-Driven Development done correctly.

—Anonymous

Software projects fail because they don’t do what customers want; or because they are late; or because they are over budget; or because they are hard to maintain and evolve; or all of the above.

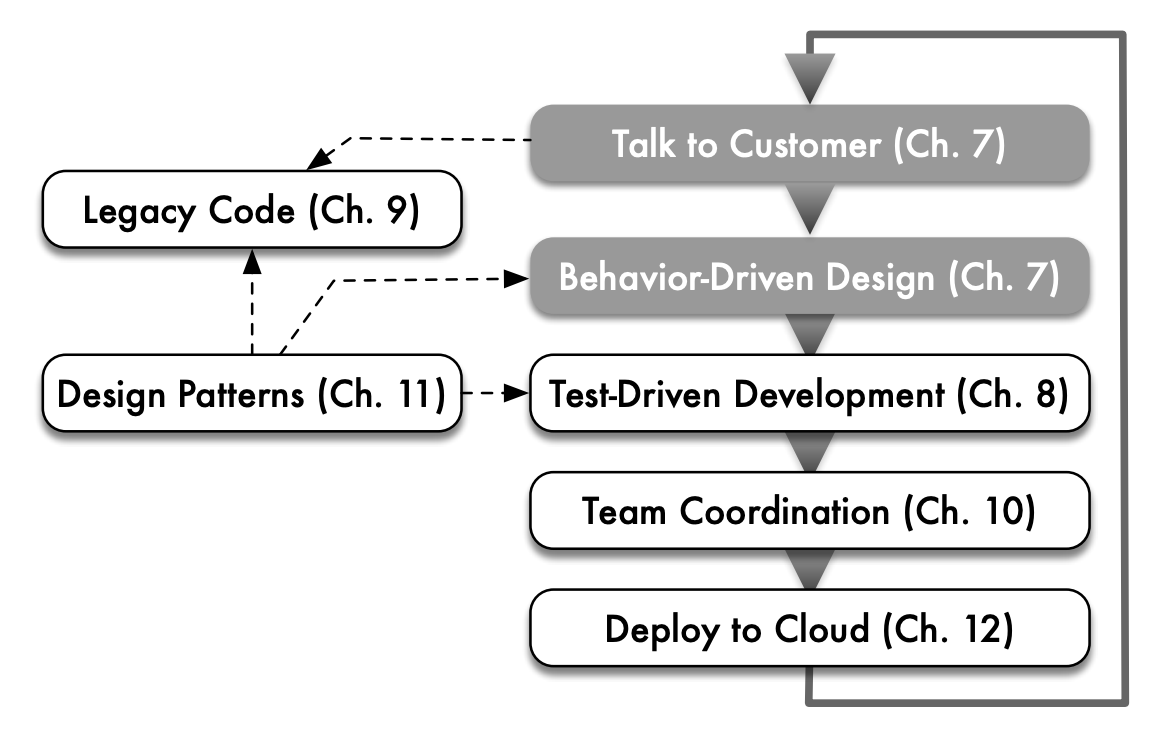

The Agile lifecycle was invented to attack these problems for many common types of software. Figure 7.1 shows one iteration of the Agile lifecycle from Chapter 1, highlighting the portion covered in this chapter. As we saw in Chapter 1, the Agile lifecycle involves:

Working closely and continuously with stakeholders to develop requirements and tests.

Maintaining a working prototype while deploying new features typically every two weeks—called an iteration—and checking in with stakeholders to decide what to add next and to validate that the current system is what they really want. Having a working prototype and prioritizing features reduces the chances of a project being late or over budget, or perhaps increasing the likelihood that the stakeholders are satisfied with the current system once the budget is exhausted!

Unlike a plan-and-document lifecycle in Chapter 1, Agile development does not switch phases (and people) over time from development mode to maintenance mode. With Agile, you are basically in maintenance mode as soon as you’ve implemented the first set of features. This approach helps make the project easier to maintain and evolve.

We start the Agile lifecycle with Behavior-Driven Design (BDD). BDD asks questions about the behavior of an application before and during development so that the stakeholders are less likely to miscommunicate. Requirements are written down as in plan-and-document, but unlike plan-and-document, requirements are continuously refined to ensure the resulting software meets the stakeholders’ desires. That is, using the terms from Chapter 1, the goal of BDD requirements is validation (build the right thing), not just verification (build the thing right).

The BDD version of requirements is user stories, which describe how the application is expected to be used. They are lightweight versions of requirements that are better suited to Agile. User stories help stakeholders plan and prioritize development. Thus, like plan-and-document, you start with requirements, but in BDD user stories take the place of design documents in plan-and-document.

By concentrating on the behavior of the application versus the implementation of application, it is easier to reduce misunderstandings between stakeholders. As we shall see in the next chapter, BDD is closely tied to Test-Driven Development (TDD), which does test implementation. In practice they work together hand-in-hand, but for pedagogical reasons we introduce them sequentially.

User stories came from the Human Computer Interface (HCI) community. They devel- oped them using 3-inch by 5-inch index cards or “3-by-5 cards,” or in countries where metric paper sizes are used, A7 cards of 74 mm by 105 mm. (We’ll see other examples of paper and pencil technology from the HCI community shortly.) These cards contain one to three sentences written in everyday nontechnical language written jointly by the customers and de- velopers. The rationale is that paper cards are nonthreatening and easy to rearrange, thereby enhancing brainstorming and prioritizing. The general guidelines for the user stories them- selves is that they must be testable, be small enough to implement in one iteration, and have business value. Section 7.2 gives more detailed guidance for good user stories.

Note that individual developers working by themselves without customer interaction don’t need these 3-by-5 cards, but this “lone wolf” developer doesn’t match the Agile philosophy of working closely and continuously with the customer.

We will use the RottenPotatoes app from Chapters 3 and 4 as the running example in this chapter and the next one. We start with the stakeholders, which are simple for this simple app:

The operators of RottenPotatoes, and

The movie fans who are end-users of RottenPotatoes.

We’ll introduce a new feature in Section 7.6, but to help understand all the mov- ing parts, we’ll start with a user story for an existing feature of RottenPotatoes so that we can understand the relationship of all the components in a simpler set- ting. The user story we picked is to add movies to the RottenPotatoes database:

Feature: Add a movie to RottenPotatoes

As a movie fan

So that I can share a movie with other movie fans

I want to add a movie to RottenPotatoes database

Scenario: Add a movie

Given I am on the RottenPotatoes home page

When I follow "Add new movie"

Then I should be on the Create New Movie page

When I fill in "Title" with "Hamilton"

And I select "PG-13" from "Rating"

And I select "July 4, 2020" as the "Released On" date

And I press "Save Changes"

Then I should be on the RottenPotatoes home page

And I should see "Hamilton"

This user story format was developed by the startup company Connextra and is named after them; sadly, this startup is no longer with us. The format is:

Feature name

As a [kind of stakeholder],

So that [I can achieve some goal],

I want to [do some task]

This format identifies the stakeholder since different stakeholders may describe the desired behavior differently. For example, users may want to link to information sources to make it easier to find the information while operators may want links to trailers so that they can get an income stream from the advertisers. All three clauses have to be present in the Connextra format, but they are not always in this order.

Self-Check 7.1.1. True or False: User stories on 3x5 cards in BDD play the same role as design requirements in plan-and-document.

True.