1.6. SaaS and Service Oriented Architecture¶

As the Web started to reach large audiences in the mid 1990s, a new idea started to emerge: rather than relying on users to install software on their computers, why not run the software centrally on Internet-based servers, and allow users to access it via a Web browser? Salesforce was arguably the first large company to fully embrace this new model, which was dubbed Software as a Service (SaaS). Examples of SaaS that many of us now use every day include searching, social networking, and watching videos. But even apps such as word processing, contact management, and calendars, for which the previously dominant software delivery model was for users to install the software on their devices, have largely migrated to SaaS. The advantages of SaaS for both users and developers explain the popularity of SaaS:

Since customers do not need to install the application, they don’t have to worry whether their hardware is the right brand or fast enough, nor whether they have the correct version of the operating system.

The data associated with the service is generally kept with the service, so customers need not worry about backing it up, losing it due to a local hardware malfunction, or even losing the whole device, such as a phone or tablet.

When a group of users wants to collectively interact with the same data, SaaS is a natural vehicle.

When data is large and/or updated frequently, it may make more sense to centralize data and offer remote access via SaaS.

Onlyasinglecopyoftheserversoftwarerunsinauniform,tightly-controlledhardware and operating system environment selected by the developer. Although different Web browsers still have some incompatible behaviors (a topic we address in Chapter 6), developers overwhelmingly avoid the compatibility hassles of distributing binaries that must run on different users’ computers.

Since the only copy of the server software is under the developers’ control, they can upgrade the software and even the hardware as long as they don’t violate the external application program interfaces (API), and they can pre-test new versions of the ap- plication on a small fraction of the real customers first, all without pestering users to upgrade their installed applications.

SaaS companies compete regularly on bringing out new features to help ensure that their customers do not abandon them for a competitor who offers a better service.

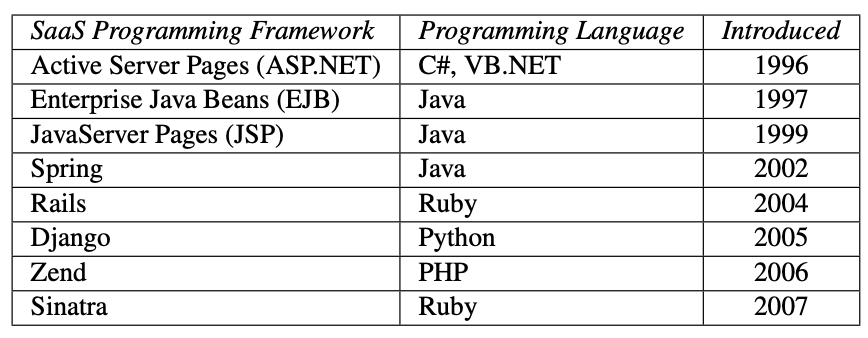

Given the popularity of SaaS, Figure 1.6 lists just a few the many programming frameworks that claim to help create SaaS applications. In this book, we use the Rails framework written in the Ruby language (“Ruby on Rails”), although the ideas we cover will work with other programming frameworks as well. We chose Rails because it came from a community that had already embraced the Agile lifecycle, so the tools support Agile particularly well. If you are not already familiar with Ruby or Rails, this gives you a chance to practice an important software engineering skill: use the right tool for the job, even if it means learning a new tool or new language! Indeed, an attractive feature of the Rails community is that its contributors routinely improve productivity by inventing new tools to automate tasks that were formerly done manually.

Note that frequent upgrades of SaaS—due to only having a single copy of the software—perfectly align with the Agile software lifecycle. Hence, Amazon, eBay, Facebook, Google, and other SaaS providers all rely on the Agile lifecycle, and traditional software companies like Microsoft are increasingly using Agile in their product development. The Agile process is an excellent match to the fast-changing nature of SaaS applications.

Despite all the advantages of SaaS, it was still missing one critical advantage in the area of software reuse. When creating SaaP, developers could make extensive use of software libraries containing code to perform tasks common to many different applications. Because these libraries were often written by others (so-called third-party libraries), they embodied the advantage of software reuse. By the mid 2000s, a similar phenomenon began to take shape in SaaS: the rise of service-oriented architecture (SOA), in which a SaaS service could call upon other services built and maintained by other developers for common tasks. Services that were highly specialized to a narrow range of tasks came to be called microservices; today’s common examples include credit card processing, search, driving directions, and more. As standards solidified for representing and interacting with such external services, the important benefit of reuse finally arrived for SaaS. Chapter 3 delves into more detail about SOA and microservices.

Of course, we have yet to address one major difference between SaaS and SaaP: the underlying hardware on which the apps will run. With SaaP, that hardware consists of the PCs of millions of individual users. In the next section we explore the underlying hardware that makes SaaS possible.

Self-Check 1.6.1. Some of Google’s most popular SaaS apps are Search, Maps, Gmail, Calendar, and Documents. For each of these apps, give one advantage of delivering the app as SaaS rather than SaaP.

Many answers are correct, but here are ours:

No user installation: Documents

Can’t lose data: Gmail, Calendar.

Users cooperating: Documents.

Large/changing datasets: Search, Maps, YouTube.

Software centralized in single environment: Search.

No field upgrades when improve app: Documents.

Self-Check 1.6.2. True or False: If you are using the Agile development process to develop SaaS apps, you could use Python and Django or languages based on the Microsoft’s .NET framework and ASP.NET instead of Ruby and Rails.

True. Programming frameworks for Agile and SaaS include Django and ASP.NET.