12.6. Improving Rendering and Database Performance With Caching¶

There are only two hard things in computer science: cache invalidation and naming things.

—Phil Karlton

The idea behind caching is simple: information that hasn’t changed since the last time it was requested can simply be regurgitated rather than recomputed. In SaaS, caching can help two kinds of computation. First, if information needed from the database to complete an action hasn’t changed, we can avoid querying the database at all. Second, if the information underlying a particular view or view fragment hasn’t changed, we can avoid re-rendering the view (recall that rendering is the process of transforming Erb with embedded Ruby code and variables into HTML). In any caching scenario, we must address two issues:

Naming: how do we specify that the result of some computation should be cached for later reuse, and name it in a way that ensures it will be used only when that exact same computation is called for?

Expiration: How do we detect when the cached version is out of date (stale) because the information on which it depends has changed, and how do we remove it from the cache? The variant of this problem that arises in microprocessor design is often referred to as cache invalidation.

Figure 12.4 shows how caching can be used at each tier in the 3-tier SaaS architecture and what

Rails entities are cached at each level. The simplest thing we could do is cache the entire HTML

page resulting from rendering a particular controller action. For example, the

MoviesController#show action and its corresponding view depend only on the attributes of the

particular movie being displayed (the @movie variable in the controller method and view

template). Figure 12.5 shows how to cache the entire HTML page for a movie, so

that future requests to that page neither access the database nor re-render the HTML, as

in Figure 12.4(b).

1# In Gemfile, include gems for page and action caching

2gem 'actionpack -page_caching'

3gem 'actionpack -action_caching'

4gem 'rails-observers'

1class MoviesController < ApplicationController

2 caches_page :show

3 cache_sweeper :movie_sweeper

4 def show

5 @movie = Movie.find(params[:id])

6 end

7end

1class MovieSweeper < ActionController::Caching::Sweeper

2 observe Movie

3 # if a movie is created or deleted, movie list becomes invalid

4 # and rendered partials become invalid

5 def after_save(movie) ; invalidate ; end

6 def after_destroy(movie) ; invalidate ; end

7 private

8 def invalidate

9 expire_action :action => ['index', 'show']

10 expire_fragment 'movie'

11 end

12end

Of course, this is unsuitable for controller actions protected by before-filters, such as

pages that require the user to be logged in and therefore require executing the controller

filter. In such cases, changing caches_page to caches_action will still execute any filters

but allow Rails to deliver a cached page without consulting the database or re-rendering

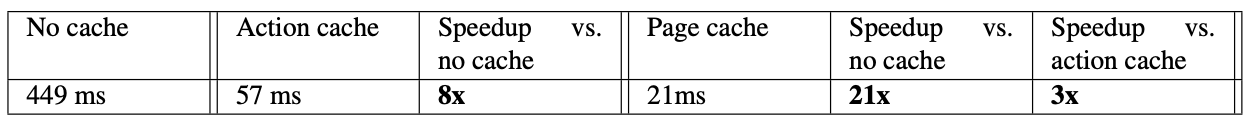

views, as in Figure 12.4(c). Figure 12.7 shows the benefits of page and action caching for

this simple example. Note that in Rails page caching, the name of the cached object ignores

embedded parameters in URIs such as /movies?ratings=PG+G, so parameters that affect how the

page would be displayed should instead be part of the RESTful route, as in /movies/ratings/ PG+G.

An in-between case involves action caching in which the main page content doesn’t change, but

the layout does. For example, your app/views/layouts/application.html.erb may include a message

such as “Welcome, Alice” contain- ing the name of the logged-in user. To allow action caching to

work properly in this case, passing :layout=>false to caches_action will result in the layout

getting fully re-rendered but the action (content part of the page) taking advantage of the

action cache. Keep in mind that since the controller action won’t be run, any such dynamic

content appearing in the layout must be set up in a before-filter.

Page-level caching isn’t useful for pages whose content changes dynamically. For example,

the list of movies page (MoviesController#index action) changes when new movies are added

or when the user filters the list by MPAA rating. But we can still benefit from caching by

observing that the index page consists largely of a collection of table rows, each of which

depends only on the attributes of one specific movie. Indeed, that observation allowed us to

factor out the code for one row into a partial, as Figure 5.1 (Section 5.1) showed. Figure 12.6

shows how a trivial change to that partial caches the rendered HTML fragment corresponding to

each movie.

1<% cache(movie) do %>

2 <div class="row">

3 <div class="col-8"> <%= link_to movie.title, movie_path(movie) %> </div>

4 <div class="col-2"> <%= movie.rating %> </div>

5 <div class="col-2"> <%= movie.release_date.strftime('%F') %> </div>

6 </div>

7<% end %>

A convenient shortcut provided by Rails is that if the argument to cache is an ActiveRecord

object whose table includes an updated_at or updated_on column, the cache will auto-expire a

fragment if its table row has been updated since the fragment was first cached. Nonetheless,

for clarity, line 10 of the sweeper in Figure 12.5 shows how to explicitly expire a fragment

whose name matches the argument of cache whenever the underlying movie object is saved or

destroyed.

Unlike action caching, which avoids running the controller action at all, checking the fragment

cache occurs after the controller action has run. Given this fact, you may already be wondering

how fragment caching helps reduce the load on the database. For example, suppose we add a partial

to the list of movies page to display the @top_5 movies based on

average review scores, and we add a line to the index controller action to set up the variable:

1<!-- a cacheable partial for top movies -->

2<%- cache('top_moviegoers') do %>

3 <ul id="topmovies">

4 <%- @top_5.each do |movie| %>

5 <li> <%= moviegoer.name %> </li>

6 <% end %>

7 </ul>

8<% end %>

1class MoviegoersController < ApplicationController

2 def index

3 @movies = Movie.all

4 @top_5 = Movie.joins(:reviews).group('movie_id').

5 order("AVG(potatoes) DESC").limit(5)

6 end

7end

Action caching is now less useful, because the index view may change when a new movie is

added or when a review is added (which might change what the top 5 reviewed movies are).

If the controller action is run before the fragment cache is checked, aren’t we negating

the benefit of caching, since setting @top_5 in lines 4–5 of the controller method causes

a database query?

Surprisingly, no. In fact, lines 4–5 don’t cause a query to happen: they construct an object

that can do the query if it’s ever asked for the result! This is called lazy evaluation, an

enormously powerful programming-language technique that comes from the lambda calculus

underlying functional programming. Lazy evaluation is used in Rails’ ActiveRelation (ARel)

subsystem, which is used by ActiveRecord. The actual database query doesn’t happen until

each is called in line 4 of of the partial, because that’s the first time the ActiveRelation

object is asked to produce a value. But since that line is inside the cache block starting

on line 2, if the fragment cache hits, the line will never be executed and therefore the

database will never be queried. Of course, you must still include logic in your cache sweeper

to correctly expire the top-5-movies fragment when a new review is added.

In summary, both page- and fragment-level caching reward our ability to separate things that change (non-cacheable units) from those that stay the same (cacheable units). In page or action caching, split controller actions protected by before-filters into an “unprotected” action that can use page caching and a filtered action that can use action caching. (In an extreme case, you can even enlist a content delivery network (CDN) such as Amazon CloudFront to replicate the page at hundreds of servers around the world.) In fragment caching, use partials to isolate each noncacheable entity, such as a single model instance, into its own partial that can be fragment-cached.

Self-Check 12.6.1. We mentioned that passing :layout=>false to caches_action

provides most of the benefit of action caching even when the page layout contains dynamic

elements such as the logged-in user’s name. Why doesn’t the caches_page method also allow

this option?

Since page caching is handled by the presentation tier, not the logic tier, a hit in the page cache means that Rails is bypassed entirely. The presentation tier has a copy of the whole page, but only the logic tier knows what part of the page came from the layout and what part came from rendering the action