8.2. Anatomy of a Test Case: Arrange, Act, Assert¶

We begin with a few definitions. Following the terminology in the fairly widely used xUnit Test Patterns (Meszaros 2007), we refer to the object being tested as the system under test (SUT), whether that “object” is a single method, a group of methods, or even the entire application. That is, SUT is defined from the point of view of the test. The goal of a single test case for some SUT is to check that some specific behavior happens (for example, the return value from a function matches an expected result) or doesn’t happen (for example, passing an empty string to a string comparison function doesn’t result in an error or exception). A collection of test cases is called a test suite. A code base usually has several test suites, corresponding to different kinds of tests, as we describe later in Section 8.7.

In this section we focus on unit tests, the finest-grained test cases, for which the SUT is a single method. In particular, if the method being tested does not call any other methods to help do its job, we say it is a leaf method. Since even a leaf method may have multiple testable behaviors, a single method may be the subject of multiple test cases.

A unit test is conceptually simple: call a method, and verify some aspect of its behavior. But even leaf methods usually require establishing some preconditions before exercising the code. For example, when testing a method that combines two lists into a single sorted list, we need to create the two lists that will be provided as input. We then exercise the SUT, and finally check whether the particular behavior we were looking for was correctly exhibited.

In general, then, every test case in a suite follows the same structure of Arrange, Act, Assert:

Arrange: create any necessary preconditions for the test case, such as setting values of variables that affect the behavior of the SUT.

Act: exercise the SUT.

Assert: verify that the result or behavior matches what was expected.

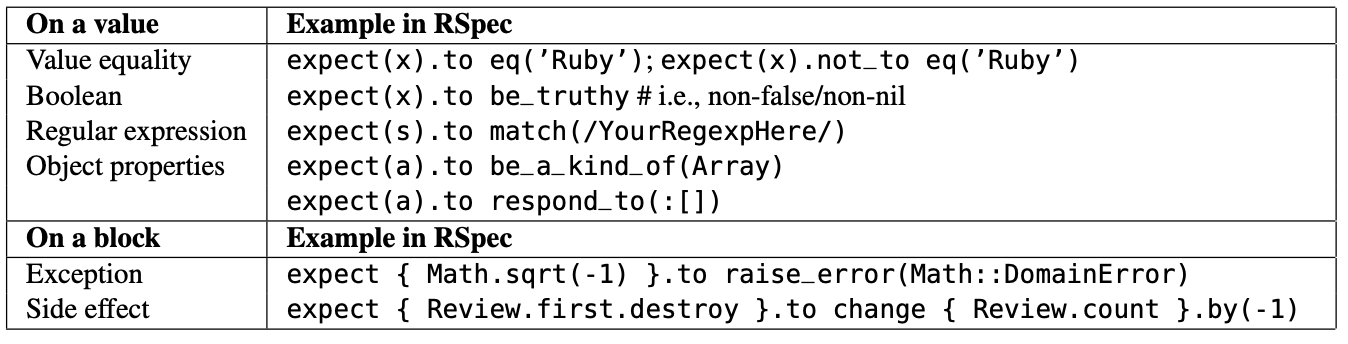

The general form of an assertion or expectation is “Expect expression to satisfy predicate”. An example of a simple

predicate is an equality check: “Expect the return value of Math.sqrt(49) to equal 7”. As Figure 8.2 shows, other

kinds of assertions deal with both inspecting output values and checking non-output-value-related behaviors.

The easiest unit tests to write are those for which the SUT is a method that is a pure function—one that has no side effects and whose return value is always the same for the same arguments. The only thing a test case needs to do is choose some inputs, call the method, and check the returned value. For example, consider a hypothetical method leap? that accepts an integer and returns a truthy value if and only if that integer corresponds to a leap year (that is, it is either a multiple of 400, or a multiple of 4 but not 100). So, for example, 2000 and 2004 are leap years, but 1900 is not. Since exhaustive testing (trying every possible input) is clearly infeasible, how do we choose which input values to use for our test cases?

A good guideline in such cases is to use input values that would cause the calculation performed in the method to follow different code paths. Given the above rule for leap years, by inspection we can deduce four categories, as Figure 8.3 shows.

A “pure” TDD workflow for developing a function that detects leap years might therefore proceed as follows. Choose any

value in category 1 above, and write a test case that asserts that the return value of leap? is falsy when called with

that value. The test fails because leap? doesn’t yet exist, so write just enough of leap? to make that case pass. Next,

choose a value in category 2, write the corresponding test, and when it fails, modify leap? so that now both tests pass.

Continue until all categories are covered.

You might object that leap? is such a simple leaf method, and its functionality so well-circumscribed, that you might

as well write the entire method at once along with the four test cases, rather than going through the motions of

developing each test case incrementally. That’s not an unreasonable objection, and as with other Agile practices, “pure”

TDD is an ideal to strive for even if you do not always follow it to the letter. But with methods that have more complex

behaviors, TDD is a valuable way to proceed methodically.