9.4. Comments and Commits: Documenting Code¶

Not only does legacy code often lack tests and good documentation, but its comments are often missing or inconsistent with the code. Thus far, we have not offered advice on how to write good comments, as we assume you already know how to write good code in this book. We now offer a brief sermon on comments, so that once you write successful characterization tests you can capture what you’ve learned by adding comments to the legacy code. Good comments have two properties:

They document things that aren’t obvious from the code.

They are expressed at a higher level of abstraction than the code.

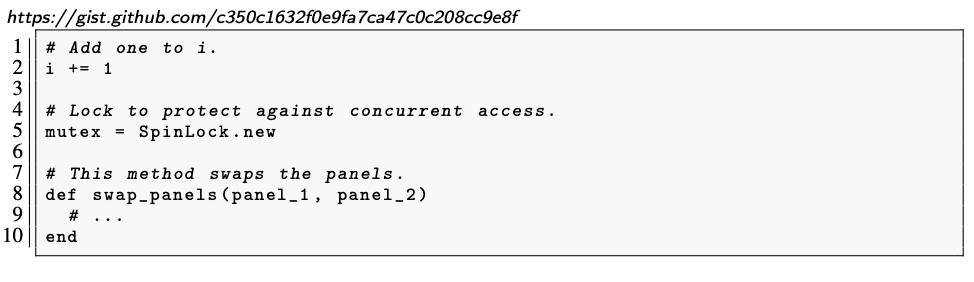

Figure 9.8 shows examples of comments that violate both properties, and Figure 9.9 shows a better example.

# Good Comment:

# Scan the array to see if the symbol exists

# Much better than:

# Loop through every array index, get the

# third value of the list in the content to

# determine if it has the symbol we are looking

# for. Set the result to the symbol if we

# find it.

First, if you write comments as you code, much of what your code does is surely obvious to you, since you just wrote it. (Alas, not commenting as you go is a common defect of legacy code.) But if you or someone else reads your code later, long after you’ve forgotten those design ideas, comments should help you remember the non-obvious reasons you wrote the code the way you did. Examples of non-obvious things include the units for variables, code invariants, subtle problems that required a particular implementation, or unusual code that is there solely to work around some bug or account for a non-obvious boundary condition or corner case. In the case of legacy code, you are trying to add comments to document what went through another programmer’s mind; once you figure it out, be sure to write it down before you forget!

Second, comments should raise the level of abstraction from the code. The programmer’s goal is to write classes and other code that hides complexity; that is, to make it easier for others to use this existing code rather than re-create it themselves. Comments should therefore address concerns such as: What do I need to know to invoke this method? Are there preconditions, assumptions, or caveats? Among other jobs, a comment should provide enough of this information that someone who wants to call an existing class or method doesn’t have to read its source code to figure these things out.

These guidelines are also generally true for commit messages, which you supply whenever you commit a set of code changes. However, one important principle is that you shouldn’t put information in a commit message that a future developer will need to know while working on the code. Historical information—why a certain function was deleted or refactored, for example—is appropriate for including in a commit message. But information that a developer would need to know to use the code as it exists now should be in a comment, where the developer cannot fail to see it when they go to edit the code.

As with many other elements of Agile, when a process isn’t working smoothly, it’s trying to tell you something about your code. For example, we saw in Chapter 8 that when a test is hard to write due to the need for extensive mocking and stubbing, the test is trying to tell you that your code is not testable because it’s poorly factored. Similarly here: if following the above guideline about comments vs. commits means you find yourself writing lots of cautionary caveats in the comments, your code is telling you that it might benefit from a refactoring cleanup so that you wouldn’t need to post so many warning signs for the next developer who comes along with the intention of modifying it.

While virtually every other software engineering sermon in this book is paired with a tool that makes it easy for you to stay on the true path and for others to check if you have strayed, this is not the case for comments and commit messages. The only enforcement mechanism beyond self-discipline is inspection, which we discuss in Sections 10.4 and 10.7.

Self-Check 9.4.1. True or False: One reason legacy code is long lasting is because it typically has good comments.

False. We wish it were true. Comments are often missing or inconsistent with the code, which is one reason it is called legacy code rather than beautiful code.