1.9. Beautiful vs. Legacy Code¶

To me programming is more than an important practical art. It is also a gigantic undertaking in the foundations of knowledge.

—Grace Murray Hopper

Unlike hardware, software is expected to grow and evolve over time. Whereas hardware designs must be declared finished before they can be manufactured and shipped, initial software designs can easily be shipped and later upgraded over time. Basically, the cost of upgrade in the field is astronomical for hardware and affordable for software.

Hence, software can achieve a high-tech version of immortality, potentially getting better over time while generations of computer hardware decay into obsolescence. The drivers of software evolution are not only fixing faults, but also adding new features that customers request, adjusting to changing business requirements, improving performance, and adapting to a changed environment. Software customers expect to get notices about and install improved versions of the software over the lifetime that they use it, perhaps even submitting bug reports to help developers fix their code. They may even have to pay an annual maintenance fee for this privilege!

Just as novelists fondly hope that their brainchild will be read long enough to be labeled a classic—which for books is 100 years!—software engineers should hope their creations would also be long lasting. Of course, software has the advantage over books of being able to be improved over time. In fact, a long software life often means that others maintain and enhance it, letting the creators of original code off the hook.

This brings us to a few terms we’ll use throughout the book. The term legacy code refers to software that, despite its old age, continues to be used because it meets customers’ needs. Sixty percent of software maintenance costs are for adding new functionality to legacy software, vs. only 17% for fixing bugs, so legacy software is successful software.

The term “legacy” has a negative connotation, however, in that it indicates that the code is difficult to evolve because it has an inelegant design or uses antiquated technology. In contrast to legacy code, we use the term beautiful code to indicate long-lasting code that is easy to evolve. The worst case is not legacy code, however, but unexpectedly short-lived code that is soon discarded because it doesn’t meet customers’ needs. We’ll highlight examples that lead to beautiful code with the Mona Lisa icon. Similarly, we’ll highlight text that deals with legacy code using an abacus icon, which is certainly a long-lasting but little changed calculating device.

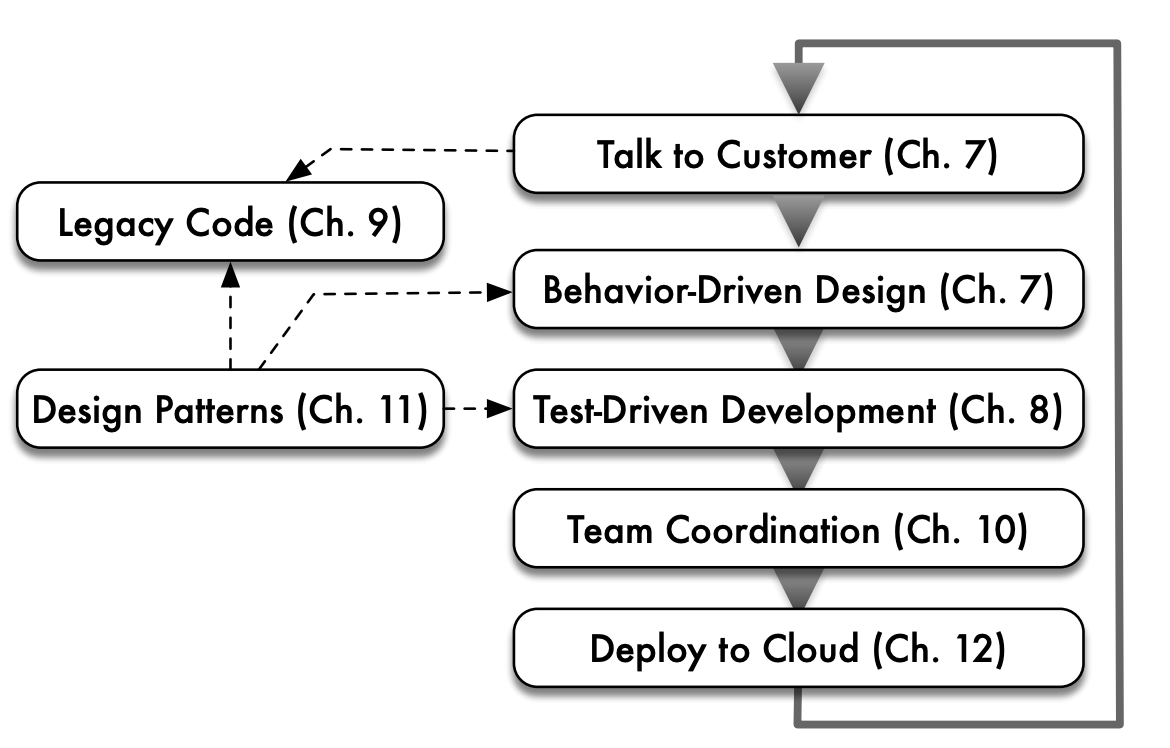

In the following chapters, we show examples of both beautiful code and legacy code that we hope will inspire you to make your designs simpler to evolve. Surprisingly, despite the widely accepted importance of enhancing legacy software, this topic is traditionally ignored in college courses and textbooks. We feature such software in this book for three reasons. First, you can reduce the effort to build a program by finding existing code that you can reuse. One supplier is open source software. Second, it’s advantageous to learn how to build code that makes it easier for successors to enhance, since such code is more likely to enjoy a long life. Finally, unlike Plan-and-Document, in Agile you revise code continuously to improve the design and to add functionality starting with the second iteration. Thus, the skills you practice in Agile are exactly the ones you need to evolve legacy code—no matter how it was created—and the dual use of Agile techniques makes it much easier for us to cover legacy code within a single book.

Self-Check 1.9.1. Programmers rarely set out to write bad code. Given the ideas of Section 1.5 about productivity, explain briefly how software written a long time ago that was considered high quality at the time might be viewed as difficult-to-maintain legacy software today.

Because of the continuously increasing level of abstraction of software tools, developers today can often create the same functionality in far fewer (and more beautiful) lines of code than would have been possible a few decades ago, so by comparison the old code is harder to maintain, even though at the time it was written it may have represented the state of the art. Doubtless the code we write today will be viewed as archaic in another few decades!