2.2. Pair Programming¶

Interviewer: At Google, you share an office, and you even code together.

Sanjay: We usually sit, and one of us is typing and the other is looking on, and we’re chatting all the time about ideas, going back and forth.

—Interview with Jeff Dean and Sanjay Ghemawat, creators of MapReduce (Hoffmann 2013)

The name Extreme Programming (XP), which is the variant of the Agile lifecycle we follow in this book, suggests a break from the way software was developed in the past. One new option in this brave new software world is pair programming. The goal is improved software quality by having more than one person developing the same code. But while pair programming emerged as a practice used by Agile teams and developers, your authors believe it’s also a way to accelerate the learning of a new language and framework. That is why we introduce it in this chapter, whose theme is learning how to learn new languages and frameworks.

Although pair programming is properly considered a software engineering process rather than being associated with a particular language, we introduce it here to encourage its use early, and especially while learning a new language. As the name suggests, in pair program- ming two developers share one computer. Each takes on a different role:

The driver enters the code and thinks tactically about how to complete the current task, explaining his or her thoughts out loud as appropriate while typing.

The observer or navigator—following the automobile analogy more closely—reviews each line of code as it is typed in, and acts as a safety net for the driver. The observer is also thinking strategically about future problems that will need to be addressed, and makes suggestions to the driver.

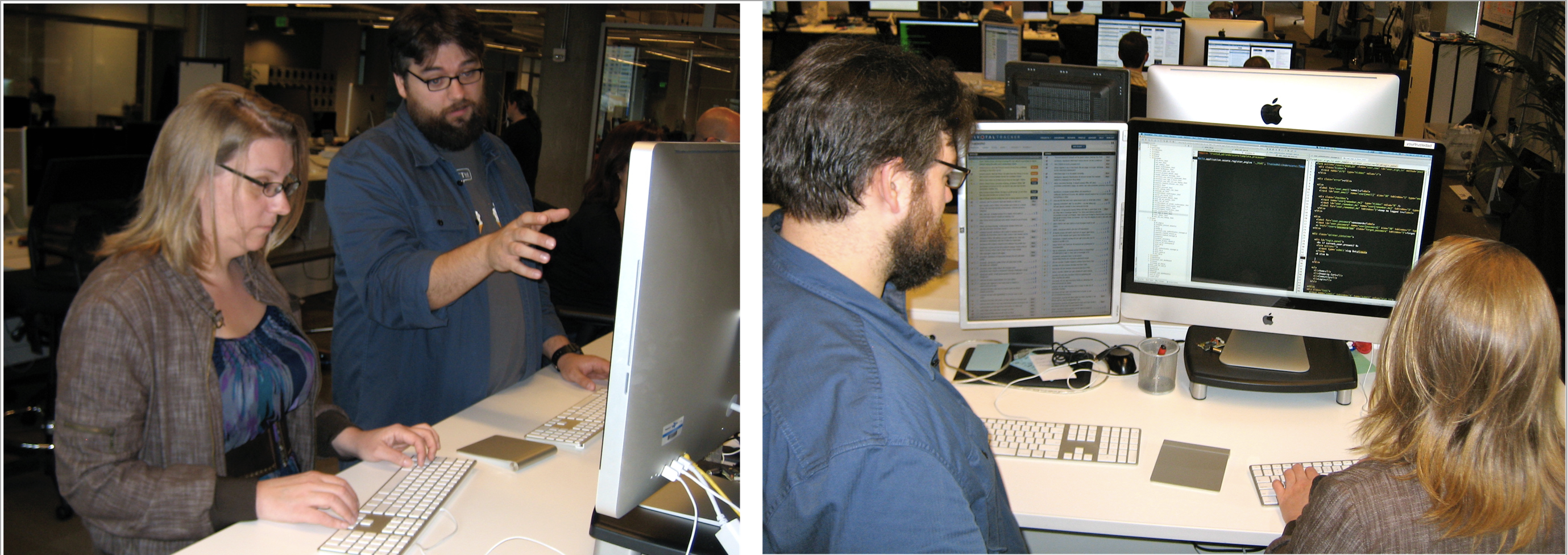

Normally a pair will take alternate driving and observing as they perform tasks. Figure 2.1, shows engineers at Pivotal Labs—makers of Pivotal Tracker—who spend most of the day doing pair programming.(Moore 2011)

Pair programming is cooperative, and should involve a lot of talking. It focuses effort to the task at hand, and two people working together increases the likelihood of following good development practices. If one partner is silent or checking email, then it’s not pair programming, just two people sitting near each other.

Pair programming has the side effect of transferring knowledge between the pair, including programming idioms, tool tricks, company processes, customer desires, and so on. Thus, to widen the knowledge base, some teams purposely swap partners per task so that eventually everyone is paired together. For example, promiscuous pairing of a team of four leads to six different pairings.

The studies of pair programming versus solo programming support the claim of reduced development time and improvement in software quality. For example, (Cockburn and Williams 2001) found a 20% to 40% decrease in time and that the initial code failed to 15% of the tests instead of 30% by solo programmers. However, it took about 15% more hours collectively for the pair of programmers to complete the tasks versus the solo programmers. The majority of professional programmers, testers, and managers with 10 years of experience at Microsoft reported that pair programming worked well for them and produced higher-quality.(Begel and Nagappan 2008) A study of pair programming studies concludes that pair programming is quicker when programming task 2009) complexity is low—perhaps one point tasks on the Tracker scale—and yields code solutions of higher 2010) quality when task complexity is high, or three points on our Tracker scale. In both cases, it took 2011) more effort than do solo programmers.(Hannay et al. 2009)

The experience at Pivotal Labs suggests that these studies may not factor in the negative impact on productivity of the distractions of our increasingly interconnected modern world: email, Twitter, Facebook, and so on. Pair programming forces both programmers to pay attention to the task at hand for hours at a time. Indeed, new employees at Pivotal Labs go home exhausted since they were not used to concentrating for such long stretches.

Even if pair programming takes more effort, one way to leverage the productivity gains from Agile and Rails is to “spend” it on pair programming. Having two heads develop the code can reduce the time to market for new software or improve quality of end product. We recommend you try pair programming to see if you like it, which some developers love.

Self-Check 2.2.1. True or False: Research suggests that pair programming is quicker and less expensive than solo programming.

False: While there have not been careful experiments that would satisfy human subject experts, and it is not clear whether they account for the lack of distractions when pair program- ming, the current consensus of researchers is that pair programming is more expensive—more programmer hours per tasks—than solo programming.

Self-Check 2.2.2. True or False: A pair will eventually figure out who is the best driver and who is the best observer, and then stick primarily to those roles.

False: An effective pair will alternate between the two roles, as it’s more beneficial (and more fun) for the individuals to both drive and observe.