8.1. FIRST, TDD, and Red–Green–Refactor¶

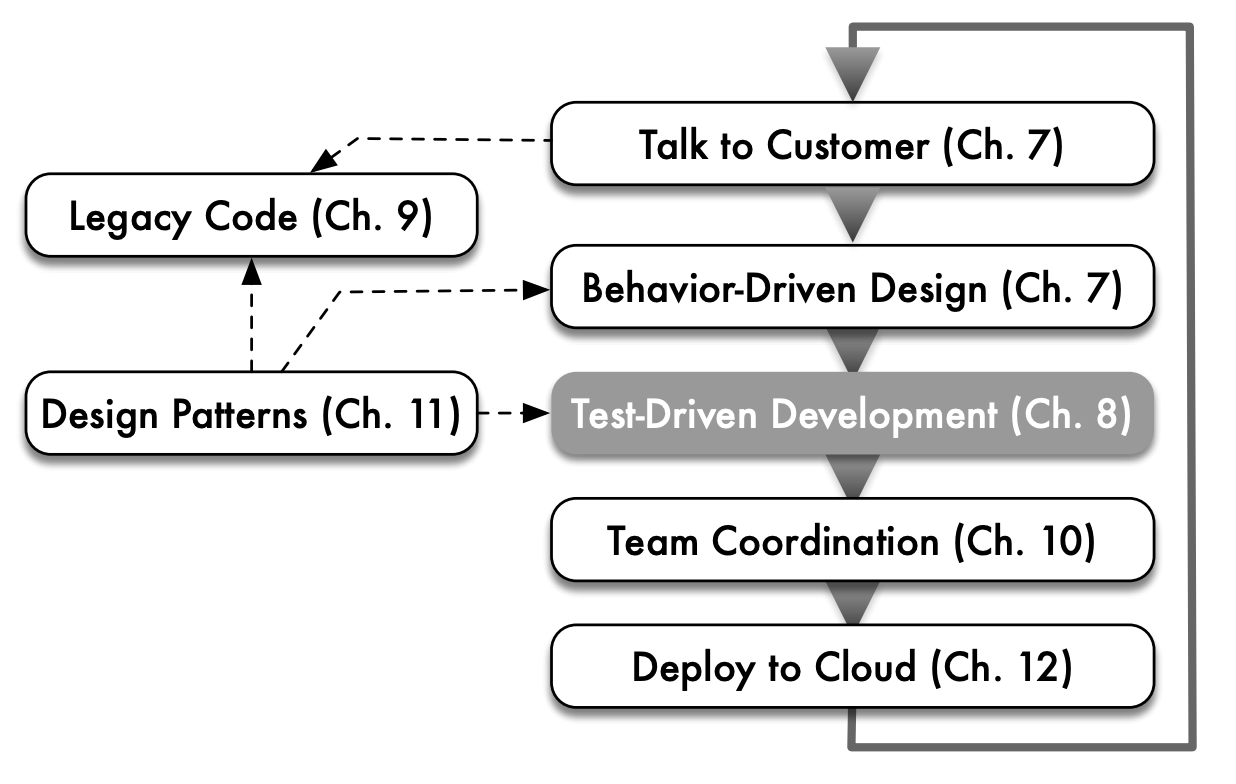

Chapter 1 introduced the Agile lifecycle and distinguished two aspects of software assurance: validation (“Did you build the right thing?”) and verification (“Did you build the thing right?”). In this chapter, we focus on verification—building the thing right—via software testing as part of the Agile lifecycle. Figure 8.1 highlights the portion of the Agile lifecycle covered in this chapter.

Although testing is only one technique used for verification, we focus on it because its role is often misunderstood, and as a result it doesn’t get as much attention as other parts of the software lifecycle. In addition, as we will see, approaching software construction from a test-centric perspective often improves the software’s readability and maintainability. In other words, testable code tends to be clear code, and vice versa. This insight may take a while to sink in if you are new to TDD, because practicing TDD may feel alien to you. We ask you again to be patient and have faith in the process!

In Agile development, developers do not “toss their code over the wall” to the Quality Assurance (QA) team, nor do QA engineers extensively exercise the software manually and file bug reports. Instead, Agile developers bear far more responsibility for testing their own code and participating in reviews, while Agile QA responsibilities focus on improving the testing tools infrastructure, helping developers make their code more testable, and verifying that customer-reported bugs are reproducible, as we’ll discuss further in Chapter 10. Furthermore, in the vast majority of tests you will write, the test code itself can determine whether the code being tested works or not, without requiring a human to manually check test output or interact with the software.

Even though Agile developers are expected to write their own tests, and those tests are expected to be automated, there is often a role for some manual testing. For example, user acceptance testing observes actual users (or QA engineers acting as “typical” users) using the product to determine whether you “built the right thing,” and operational acceptance testing may manually try additional scenarios to ensure you “built the thing right.” Both can uncover bugs that were previously undetected, some of which can then have automated tests created for them. And some visual aspects of the design, such as whether particular elements on the page render in a visually appealing way, require manual inspection. But in general, modern software quality assurance is the shared responsibility of a whole team following good processes, rather than compartmentalized in a separate group.

In this section we introduce two key ideas that underpin TDD: Red–Green–Refactor and making tests FIRST. Test-driven development (TDD) TDD advocates the use of tests to drive the development of code. When TDD is used to create new code, as in this chapter, it is sometimes referred to as test-first development. The basic TDD workflow, repeated for each created test, is known as Red–Green–Refactor and proceeds as follows.

Before you write any code, write a test for one aspect of the behavior you expect the new code will have. Since the code being tested doesn’t exist yet, writing the test forces you to think about how you wish the code would behave and interact with its collaborators if it did exist. We call this “exercising the code you wish you had.”

Red step: Run the test, and verify that it fails because you haven’t yet implemented the code necessary to make it pass (that is, the code you wish you had).

Green step: Write the simplest possible code that causes this test to pass without breaking any existing tests.

Refactor step: Look for opportunities to refactor either your code or your tests—changing the code’s structure to eliminate redundancy or repetition that may have arisen as a result of adding the new code. The tests ensure that your refactoring doesn’t introduce bugs.

How do you know when you have completed all necessary tests? If you are using BDD (Chapter 7) to drive your application development, the new code being written is presumably necessary to make one or more Cucumber scenario steps pass. When all steps in a scenario pass, you’re done.

Although TDD may feel strange at first, it tends to result in code that is not only well tested, but also more modular and easier to read than code developed separately from tests. While TDD is certainly not the only way to achieve those goals, it is difficult to end up with seriously deficient code if TDD is used correctly.

What about the tests themselves? Five principles for creating good tests are summarized by the acronym FIRST: Fast, Independent, Repeatable, Self-checking, and Timely.

Fast: it should be easy and quick to run the subset of test cases relevant to your current coding task, to avoid interfering with your train of thought.

Independent: The order in which tests run shouldn’t matter. More precisely, if no test relies on preconditions created by other tests, we can prioritize running only a subset of tests that cover recent code changes.

Repeatable: test behavior should not depend on external factors such as today’s date or on “magic constants” that will break the tests if their values change, as occurred with many 1960s programs when the year 2000 arrived due to the Y2K problem.

Self-checking: each test should be able to determine on its own whether it passed or failed, rather than relying on humans to check its output.

Timely: tests should be created or updated at the same time as the code being tested. As we’ll see, with test-driven development the tests are written immediately before the code.

Self-Check 8.1.1. Suppose step 1 in your Cucumber scenario is passing, but step 2 is failing because the code needed is not yet written. If you are practicing strict BDD and TDD, explain why you will necessarily go through one or more cycles of Red–Green–Refactor before step 2 passes.

If the code for step 2 does not yet exist, strict TDD says you should develop that code by first writing a focused test for one aspect of the code’s behavior, watching that test fail, then writing the code to make it pass.