3.2. SaaS Communication Uses HTTP Routes¶

How do SaaS clients and SaaS servers communicate? A network protocol is a set of communication rules on which agents participating in a network agree. The fundamental proto- col linking all computers on the Internet is TCP/IP, the venerable Transmission Control Protocol/Internet Protocol. TCP/IP allows a pair of communicating agents to exchange ordered sequences of bytes in both directions simultaneously (full duplex), analogous to a telephone conversation in which both parties can speak and listen at the same time. If a pro- gram at one end of the TCP/IP connection (say, the client) emits a string to the connection, the server will receive that exact string, and vice versa. TCP/IP doesn’t distinguish the roles of the agents on either side of the connection—it doesn’t care if one is the server and one is the client, or if they are peers in a peer-to-peer network—and it doesn’t place any restric- tions on what strings are communicated. It is up to the individual programs communicating over a TCP/IP connection to determine the rules of communication. As we will see, in the case of Web browsers and servers, those rules are defined by HTTP, the HyperText Transfer Protocol.

How do computers contact each other in a TCP/IP-based network? Each computer is assigned an IP address consisting of

four bytes separated by dots, such as 128.32.244.172.

Most of the time we don’t use IP addresses directly—another Internet service called Domain Name System (DNS), which has

its own protocol also based on TCP/IP, is automatically invoked to map hostnames like www.eecs.berkeley.edu to IP addresses.

When you type a site name such as www.eecs.berkeley.edu into your browser’s address bar, the browser automatically contacts

a DNS server to translate that name into an IP address, in this case 128.32.244.172. For reasons related to the design and

history of IP, the IP address 127.0.0.1 and the hostname localhost always refer to the very computer on which the app is

running. This capability lets you develop and test Web apps by connecting to the server running on your own computer: from

the client’s point of view such a server functions identically to one in the cloud backed by thousands of computers. That is,

a TCP/IP based server program provides the same abstraction to the client regardless of where the server software is running

and how it is distributed over one or many computers.

Because multiple TCP/IP-based programs can be running on the same computer simultaneously—for example, a Web server and an email server—the IP address isn’t sufficient to distinguish them. Therefore, establishing a TCP/IP connection also requires a port number from 1 to 65535 to indicate which program on the server is the intended communication partner. Some program must be listening to that port number on the server in order to accept connections. The default port for production Web servers is 80 for HTTP, or increasingly commonly, 443 for HTTPS (secure HTTP, which uses public-key cryptography to encrypt HTTP communication and protect it from eavesdroppers, as we’ll learn in Chapter 12). When you start up a development server (to test your app) in your own development environment, which port it “listens” on may be determined by the IDE you use, the framework you use (Rails uses port 3000, for example), or the manner in which you start the server.

The HTTP protocol — the rules for communication to make a request and receive a response—are well-circumscribed and may be summarized as follows:

The client initiates a TCP/IP connection to a server by specifying the IP address and port number (usually 80). If the computer at that IP address does not have an HTTP server process listening on the specified port, the client immediately experiences an error, which most browsers report as “This site can’t be reached” or “Connection re- fused.”

Otherwise, if the connection succeeds, the client immediately sends an HTTP request describing its intention to perform some operation on a resource. A resource is any entity that the server app manipulates—a Web page, an image, and a form submission that creates a new user account are all examples of resources.

The server delivers an HTTP response either satisfying the client’s request or reporting any errors that prevented the request from succeeding. The response may also include information in the form of an HTTP cookie that allows the server to correctly identify this same client on future interactions.

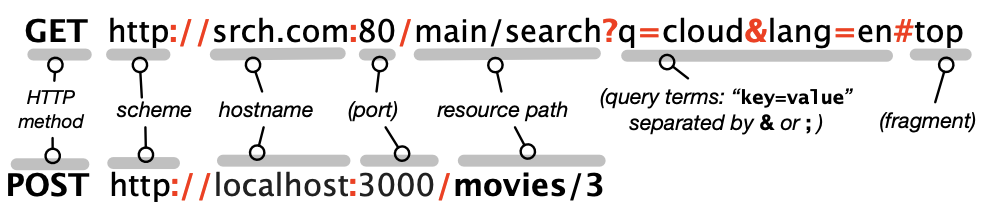

What does the client’s HTTP request in step 2 look like? An HTTP request consists of a route, zero or more headers, and possibly a request body, all of

which are just strings sent over the TCP/IP connection. As Figure 3.2 shows, an HTTP route consists of an HTTP method — usually, one of GET, POST, PUT, PATCH, or DELETE—plus a URI, or

Uniform Resource Identifier. URI. You are familiar with URIs as the strings usually beginning with http:// that you type into a browser’s address bar. Importantly,

though, it is the combination of the HTTP method and URI that defines a route: the same URI with different HTTP methods can have different meanings to a SaaS app.

We will have much more to say about the semantics of routes later in the chapter, but in general, GET typically means “deliver a copy of the resource to the client

without modifying the resource or causing any side effects,” whereas POST, PUT, PATCH, DELETE are typically used to perform an operation that creates, modifies, or

deletes a resource. When you visit a URI by typing it into a browser’s address bar, your browser performs a GET to that URI; when you submit a fill-in form, the browser

may perform either a GET or a POST to a specified URI, depending on how the page is authored. For historical reasons, most browsers don’t generate PUT, PATCH, or DELETE directly;

we will return to their use shortly.

You’ll get hands-on practice with HTTP in an upcoming CHIPS exercise, but this background will serve to orient you in advance. HTTP’s simplicity derives from two characteristics. First, HTTP is a request-response protocol: every HTTP interaction begins with the client making a request, to which the server delivers a response (unless the server crashes or the network becomes unavailable, of course!) The HTTP request must include the route and HTTP protocol version, and usually also includes some request headers that provide information about the client. The HTTP protocol version tells the server which HTTP features the client can understand, so that (for example) servers can avoid using newer HTTP features if the client only understands an older protocol version. The server reply must include the HTTP version and 3-digit status code indicating the result of the requested operation; any text following the status code on the first response line is optional and ignored, but is often used to provide a human-readable version of the status. The response also includes headers describing the rest of the response data, followed by a blank line and then the response payload itself.

Second, HTTP is a stateless protocol: every HTTP request is independent of and un- related to all previous requests. If this is so, how can a web site keep track of information such as

whether you have logged in? HTTP provides a mechanism called cookies for this purpose. The first time a client makes a request from some server, the server can include in

the response a Set-Cookie: header, containing a chunk of information that the server can use to identify this client on future HTTP requests. It is the client’s responsibility to store

that information and pass it back via a Cookie: header on every subsequent request to that same server. Analogously to a coat-check token, a cookie should be both tamper-evident and opaque

to (not interpretable by) the client, but if presented later to the server, is sufficient to identify the client, thereby enabling the concept of a continuing session between the server

and that client. Stateless protocols therefore simplify server design at the expense of more complex application design, but happily, successful frameworks such as Rails shield you from

much of this complexity.

Self-Check 3.2.1. Is DNS a client–server protocol? Why or why not?

Yes. DNS clients only ever ask for lookup services (DNS resolution) whereas DNS services only ever provide responses.

Self-Check 3.2.2. Can you make a TCP connection without specifying a port number, and if so, what happens?

All TCP connections must specify a port number. However, specific types of clients (Web browsers, email readers, and so on) have the knowledge built into them of the default port numbers for those services, so end users of such clients rarely have to know this information.

Self-Check 3.2.3. True or false: HTTP as a protocol has no concept of a “session” consist- ing of a sequence of related HTTP requests to the same site.

True. HTTP is stateless, with every request being completely independent of all other requests from the same client. Therefore a mechanism such as HTTP Cookies must be used to create the abstraction of a session.

Self-Check 3.2.4. Many HTTP servers rely on using HTTP cookies to identify a client on repeated requests to the same site, for example, to track information such as whether that user has logged in. What happens if you complete disable cookies in your browser and try to visit such a site?

Try it and see. Use a search engine to find instructions on how to (temporarily) disable cookies entirely in your browser, and try to log in to a site where you have an account. Don’t forget to re-enable cookies when you finish your experiment.