10.7. The Plan-And-Document Perspective on Managing Teams¶

In Plan-And-Document processes, project management starts with the project manager. Project managers are the bosses of the projects:

They write the contract proposal to win the project from the customer.

They recruit the development team from existing employees and new hires.

They typically write team members’ performance reviews, which shape salary in- creases.

From a Scrum perspective (Section 10.1), they act as Product Owner—the primary customer contact—and they act as Scrum Lead, as they are the interface to upper management and they procure resources for the team.

As we saw in Section 7.9, project managers also estimate costs, make and maintain the schedule, and decide which risks to address and how to overcome or avoid them.

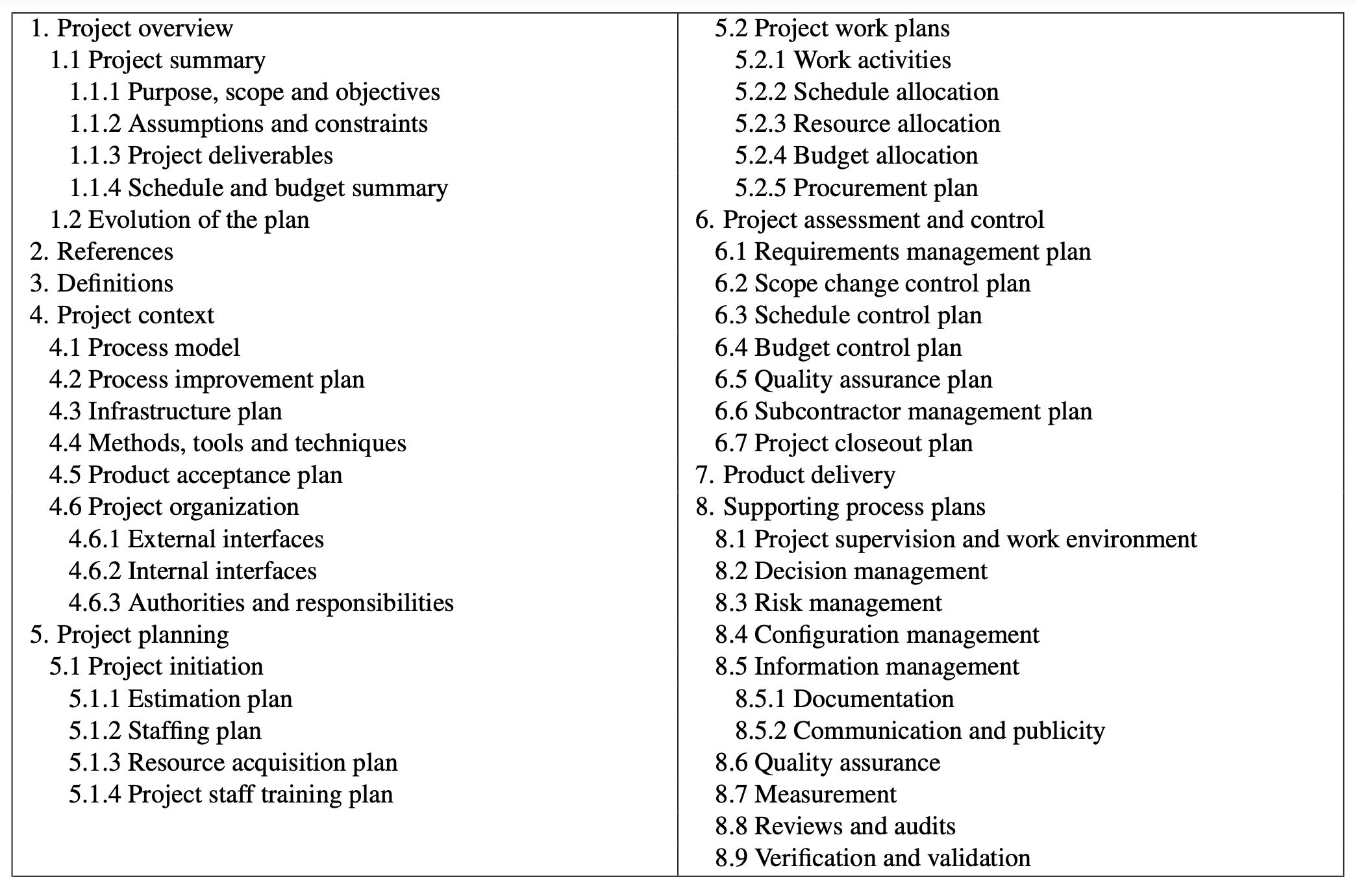

As you would expect for Plan-And-Document processes, project managers must docu- ment their project management plan. Figure 10.11 gives an outline of Project Management Plans from the corresponding IEEE standard.

As a result of all the these responsibilities, project managers receive much of the blame if projects have problems. Quoting a textbook author from his introduction to project management:

However, if a post mortem were to be conducted for every [problematic] project, it is very likely that a consistent theme would be encountered: project management was weak.

—Pressman 2010

We cover four major tasks for project managers to increase their chances of being successful:

Team size, roles, space, communication

Managing people and conflicts

Inspections and metrics

Configuration management

1. Team size, roles, space, and communication. The Plan-and-Document processes can scale to larger sizes, where group leaders report to the project manager. However, each subgroup typically stays the size of the two-pizza teams we saw in Section 10.1. Size recommendations are three to seven people (Braude and Berstein 2011) to no more than ten (Sommerville 2010). Fred Brooks gave us the reason in Chapter 7: adding people to the team increases parallelism, but also increases the amount of time each person must spend communicating. These team sizes are reasonable considering the fraction of time spent communicating.

Given we know the size of the team, members of a subgroup in Plan-and-Document processes can be given different roles in which they are expected to lead. For example (Pressman 2010):

Configuration management leader

Quality assurance leader

Requirements management leader

Design leader

Implementation leader

One surprising result is that the type of space for the team to work in affects project management. One study found that collocating the team in open space could double productivity (Teasley et al. 2000). The reasons include that team members had easy access to each other for both coordination of their work and for learning, and they could post their work artifacts on the walls so that all could see. Another study of teams in open space concludes:

One of the main drivers of success was the fact that the team members were at hand, ready to have a spontaneous meeting, advise on a problem, teach/learn something new, etc. We know from earlier work that the gains from being at hand drops off significantly when people are first out of sight, and then most severely when they are more than 30 meters apart.

—Allen and Henn 2006

While the team relies on email and texting for communicating and shares information in wikis and the like, there is also typically a weekly meeting to help coordinate the project. Recall that the goal is to minimize the time spent communicating unnecessarily, so it is important that the meetings be effective. Below is our digest of advice from the many guidelines found on the Web on how to have efficient meetings. We use the acronym SAMOSAS as a memory device; surely bringing a plate of them will make for an effective meeting!

Start and stop meeting on time.

Agenda created in advance of meeting; if there is no agenda, then cancel the meeting.

Minutes must be recorded so everyone can recall results afterwards; the first agenda item is finding a note taker.

One speaker at a time; no interruptions when another is speaking.

Send material in advance, since people read much faster than speakers talk.

Action items at end of meeting, so people know what they should do as a result of the meeting.

Set the date and time of the next meeting.

2. Managing people and conflicts. Thousands of books have been written on how to manage people, but the two most useful ones that we have found are The One Minute Manager and How to Win Friends and Influence People ( Blanchard and Johnson 1982; Carnegie 1998). What we like about the first book is that it offers short quick advice. Be clear about the goals of what you want done and how well it should be done, but leave it up to the team member how to do it to encourage creativity. When meeting with individuals to review progress, start with positive feedback to help build their confidence. Then, be honest with them about what is not going well, and what they need to do to fix it. Finally, conclude with positive feedback and encouragement to continue improving their work. What we like about the second book is that it helps teach the art of persuasion, to get people to do what you think should be done without ordering them to do it. These skills also help persuade people you cannot command: your customers and your management.

Both books are helpful when it comes to resolving conflicts within a team. Conflicts are not necessarily bad, in that it can be better to have the conflict than to let the project crash and burn. Intel Corporation labels this attitude constructive confrontation. If you have a strong opinion that a person is proposing the wrong thing technically, you are obligated to bring it up, even to your bosses. The Intel culture is to speak up even if you disagree with the highest ranked people in the room.

If conflict continues, given that Plan-and-Document processes have a project manager, that person can make the final decision. One reason the US made it to the moon in the 1960s is that a leader of NASA, Wernher von Braun, had a knack for quickly resolving conflicts on close decisions. His view was that picking an option arbitrarily but quickly was frequently better, since the choice was roughly 50-50, so that the project could move ahead rather than take the time to carefully collect all the evidence to see which choice was slightly better.

However, once a decision is made, the teams needs to embrace it and move ahead. The Intel motto for this resolution is disagree and commit: “I disagree, but I am going to help even if I don’t agree.”

3. Inspections and metrics. Inspections like design reviews and code reviews allow feedback on the system even before everything is working. The idea is that once you have a design and initial implementation plan, you are ready for feedback from developers beyond your team. Design and code reviews follow the Waterfall lifecycle in that each phase is completed in sequence before going on to the next phase, or at least for the phases of a single iteration in Spiral or RUP development.

A design review is a meeting in which the authors of program present its design. The goal of the review is to improve software quality by benefiting from the experience of the people attending the meeting. A code review is held once the design has been implemented. This peer-oriented feedback also helps with knowledge exchange within the organization and offers coaching that can help the careers of the presenters.

Shalloway suggests that formal design code reviews are often too late in the process to make a big impact on the result (Shalloway 2002). He recommends to instead have earlier, smaller meetings that he calls “approach reviews.” The idea is to have a few senior developers assist the team in coming up with an approach to solve the problem. The group brainstorms about different approaches to help find a good one.

If you plan to do a formal design review, Shalloway suggests that you first hold a “mini-design review” after the approach has been selected and the design is nearing completion. It involves the same people as before, but the purpose is to prepare for the formal review.

The formal review itself should start with a high-level description of what the customers want. Then give the architecture of the software, showing the APIs of the components. It will be important to highlight the design patterns used at different levels of abstraction (see Chapter 11). You should expect to explain why you made the decisions, and whether you considered plausible alternatives. Depending on the amount of time and the interests of those at the meeting, the final phase would be to go through the code of the implemented methods. At all these phases, you can get more value from the review if you have a concrete list of questions or issues that you would like to hear about.

One advantage of code reviews is that they encourage people outside your team to look at your comments as well as your code. As we don’t have a tool that can enforce the advice from Chapter 9 about making sure the comments raise the level of abstraction, the only enforcing mechanism is the code review.

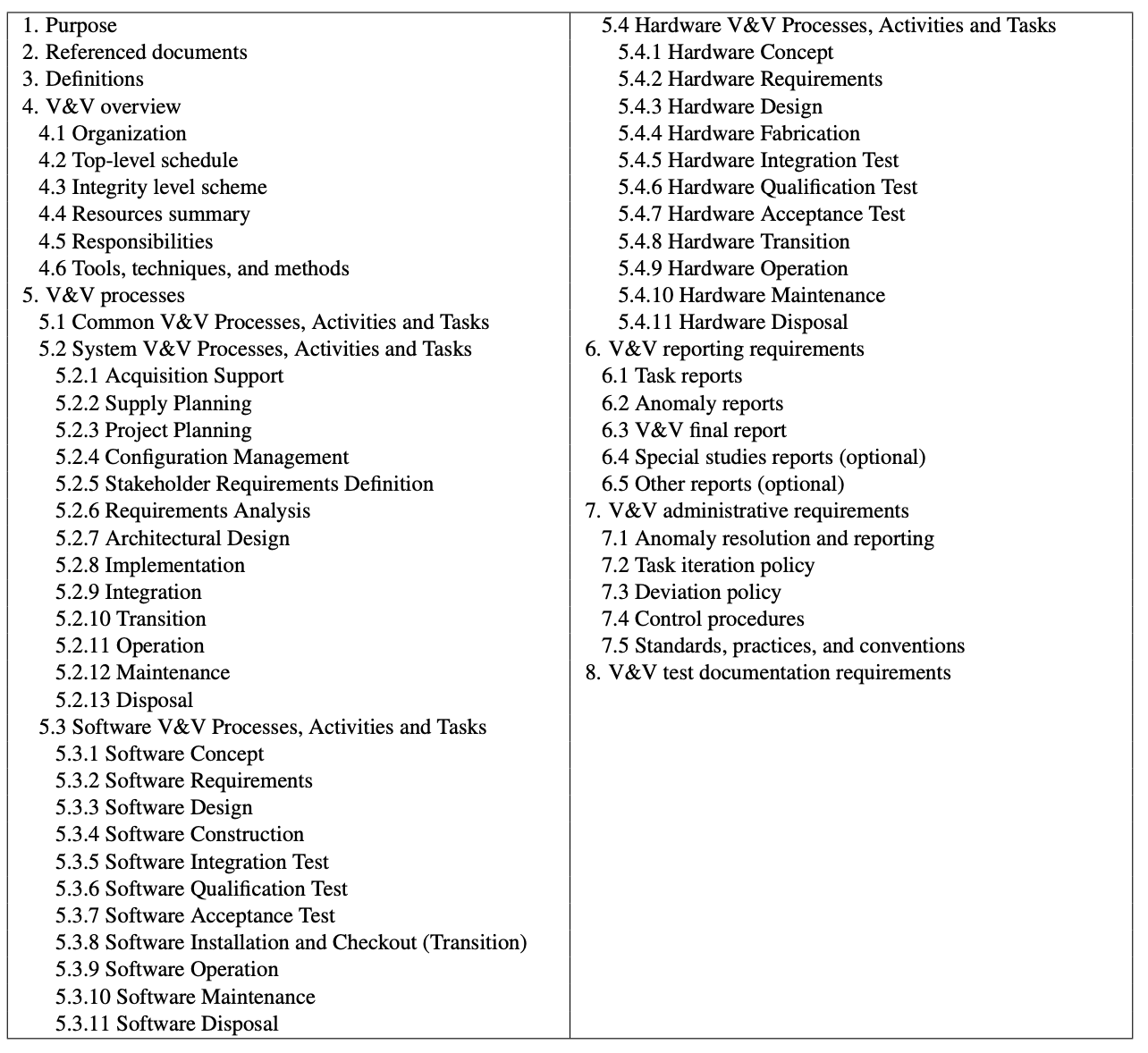

In addition to reviewing the code and the comments, inspections can give feedback on every part of the project in Plan-and-Document processes: the project plan, schedule, requirements, testing plan, and so on. This feedback helps with verification and validation of the whole project, to ensure that it is on a good course. There is even an IEEE standard on how to document the verification and validation plan for the project, which Figure 10.12 shows.

Like the algorithmic models for cost estimation (see Section 7.9), some researchers have advocated that software metrics could replace inspections or reviews to assess project quality and progress. The idea is to collect metrics across many projects in organization over time, establish a baseline for new projects, and then see how the project is doing compared to baseline. This quote captures the argument for metrics:

Without metrics, it is difficult to know how a project is executing and the quality level of the software.

—Braude and Berstein 2011

Below are sample metrics that can be automatically collected:

Code size, measured in thousands of lines of code (KLOC) or in function points (Sec- tion 7.9).

Effort, measured in person-months spent on project.

Project milestones planned versus fulfilled.

Number of test cases completed.

Defect discovery rate, measured in defects discovered via testing per month.

Defect repair rate, measured in defects fixed per month.

Other metrics can be derived from these so as to normalize the numbers to help compare results from different projects: KLOC per person-month, defects per KLOC, and so on.

The problem with this approach is that there is little evidence of correlation between these metrics that we can automatically collect and project outcomes. Ideally, the metrics would correlate and we could have much finer-grained understanding than comes from the occasional and time consuming inspections. This quote captures the argument de-emphasizing metrics:

However, we are still quite a long way from this ideal situation, and there are no signs that automated quality assessment will become a reality in the foreseeable future

—Sommerville 2010

4. Configuration management. Configuration management includes four varieties of changes, three of which we have seen before. The first is version control, sometimes also called source and configuration management (SCM), described in Sections 10.2–10.4. This variety keeps track of versions of components as they are changed. The second, system building, is closely related to the first. Tools like make assemble the compatible versions of components into an executable program for the target system. The third variety is release management, which we cover in Chapter 12. The last is change management, which comes from change requests made by customers and other stakeholders to fix bugs or to improve functionality (see Section 9.7).

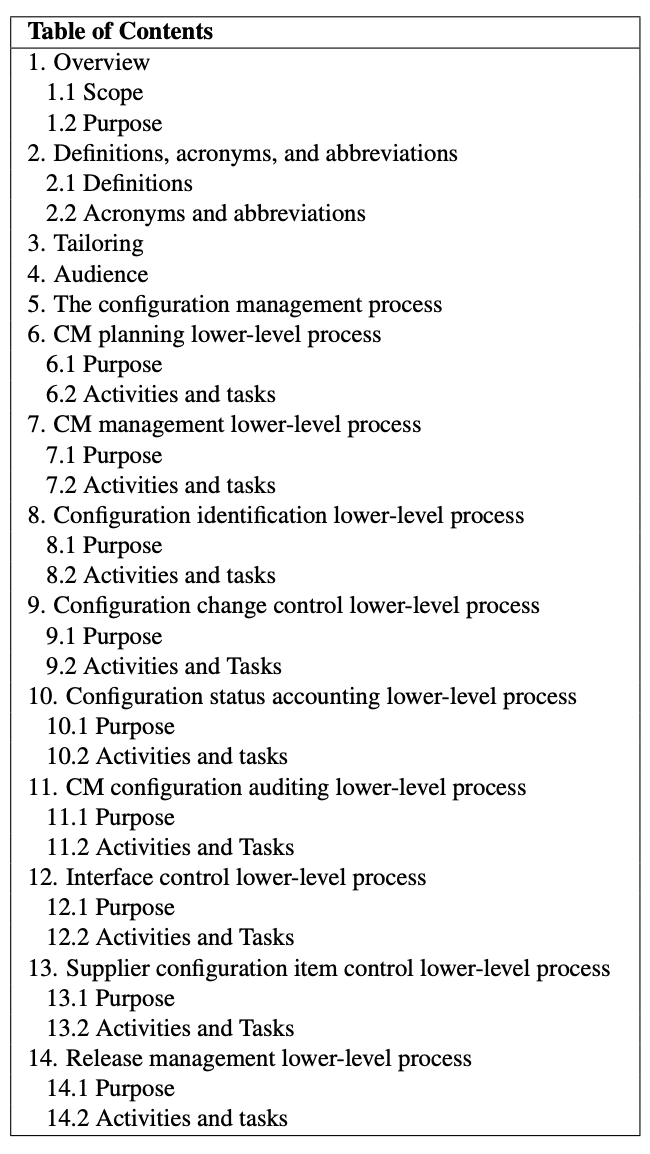

As you surely expect by now, IEEE has a standard for Configuration Management. Figure 10.13 shows its table of contents.

Self-Check 10.7.1. Compare the size of teams in Plan-and-Document processes versus Agile processes.

Plan-and-Document processes can form hierarchies of subgroups to create a much larger project, but each subgroup is basically the same size as a “two-pizza” team for Agile.

Self-Check 10.7.2. True or False: Design reviews are meetings intended to improve the quality of the software product using the wisdom of the attendees, but they also result in technical information exchange and can be highly educational for junior members of the organization, whether presenters or just attendees.

True.