9.1. What Makes Code “Legacy” and How Can Agile Help?¶

1. Continuing Change: [software] systems must be continually adapted or they become progressively less satisfactory

—Lehman’s first law of software evolution

As Chapter 1 explained, legacy code stays in use because it still meets a customer need, even though its design or implementation may be outdated or poorly understood. In this chapter we will show not only how to explore and come to understand a legacy codebase, but also how to apply Agile techniques to enhance and modify legacy code. Figure 9.1 highlights this topic in the context of the overall Agile lifecycle.

Maintainability is the ease with which a product can be improved. In software engineering, maintenance consists of four categories (Lientz et al. 1978):

Corrective maintenance: repairing defects and bugs

Perfective maintenance: expanding the software’s functionality to meet new customer requirements

Adaptive maintenance: coping with a changing operational environment even if no new functionality is added; for example, adapting to changes in the production hosting environment

Preventive maintenance: improving the software’s structure to increase future maintainability.

Practicing these kinds of maintenance on legacy code is a skill learned by doing: we will provide a variety of techniques you can use, but there is no substitute for mileage. That said, a key component of all these maintenance activities is refactoring, a process that changes the structure of code (hopefully improving it) without changing the code’s functionality. The message of this chapter is that continuous refactoring improves maintainability. Therefore, a large part of this chapter will focus on refactoring.

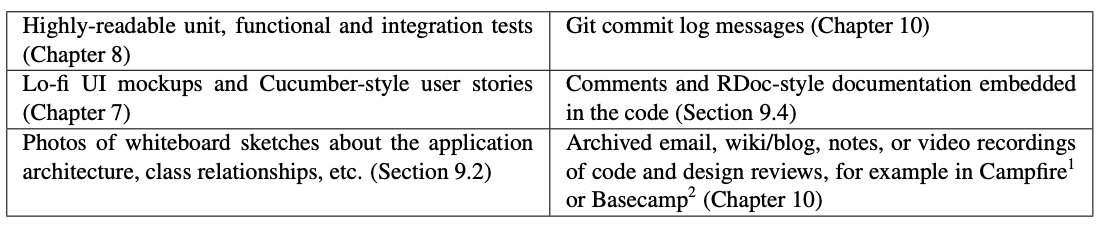

Any piece of software, however well-designed, can eventually evolve beyond what its original design can accommodate. This process leads to maintainability challenges, one of which is the challenge of working with legacy code. Some developers use the term “legacy” when the resulting code is poorly understood because the original designers are long gone and the software has accumulated many patches not explained by any current design documents. A more jaded view, shared by some experienced practitioners (Glass 2002), is that such documents wouldn’t be very useful anyway. Once development starts, necessary design changes cause the system to drift away from the original design documents, which don’t get updated. In such cases developers must rely on informal design documents such as those that Figure 9.2 lists.

How can we enhance legacy software without good documentation? As Michael Feathers writes in Working Effectively With Legacy Code (Feathers 2004), there are two ways to make changes to existing software: Edit and Pray or Cover and Modify. The first method is sadly all too common: familiarize yourself with some small part of the software where you have to make your changes, edit the code, poke around manually to see if you broke anything (though it’s hard to be certain), then deploy and pray for the best.

In contrast, Cover and Modify calls for creating tests (if they don’t already exist) that cover the code you’re going to modify and using them as a “safety net” to detect unintended behavioral changes caused by your modifications, just as regression tests detect failures in code that used to work. The cover and modify point of view leads to Feathers’s more precise definition of “legacy code”, which we will use: code that lacks sufficient tests to modify with confidence, regardless of who wrote it and when. In other words, code that you wrote three months ago on a different project and must now revisit and modify might as well be legacy code.

Happily, the Agile techniques we’ve already learned for developing new software can also help with legacy code . Indeed, the task of understanding and evolving legacy software can be seen as an example of “embracing change” over longer timescales. If we inherit well-structured software with thorough tests, we can use BDD and TDD to drive addition of functionality in small but confident steps. If we inherit poorly-structured or undertested code, we need to “bootstrap” ourselves into the desired situation in four steps:

Identify the change points, or places where you will need to make changes in the legacy system. Section 9.2 describes some exploration techniques that can help, and introduces one type of Unified Modeling Language (UML) diagram for representing the relationships among the main classes in an application.

If necessary, add characterization tests that capture how the code works now, to establish a baseline “ground truth” before making any changes. Section 9.3 explains what these tests are and how to create them using tools you’re already familiar with.

Determine whether the change points require refactoring to make the existing code more testable or accommodate the required changes, for example, by breaking dependencies that make the code hard to test. Section 9.6 introduces a few of the most widely-used techniques from the many catalogs of refactorings that have evolved as part of the Agile movement.

Once the code around the change points is well factored and well covered by tests, make the required changes, using your newly-created tests as regressions and adding tests for your new code as in Chapters 7 and 8.

Self-Check 9.1.1. Why do many software engineers believe that when modifying legacy code, good test coverage is more important than detailed design documents or well-structured code?

Without tests, you cannot be confident that your changes to the legacy code preserve its existing behaviors.