9.9. Concluding Remarks: Continuous Refactoring¶

A ship in port is safe, but that’s not what ships are built for.

—Admiral Grace Murray Hopper

As we said in the opening of the chapter, modifying legacy code is not a task to be undertaken lightly, and the techniques required must be honed by experience. The first time is always the hardest. But fundamental skills such as refactoring help with both legacy code and new code, and as we saw, there is a deep connection among legacy code, refactoring, and testability and test coverage. We took code that was neither good nor testable—it scored poorly on complexity metrics and code smells, and isolating behaviors for unit testing was awkward—and refactored it into code that has much better metric scores, is easier to read and understand, and is easier to test. In short, we showed that good methods are testable and testable methods are good. We used refactoring to beautify existing code, but the same techniques can be used when performing the enhancements themselves. For example, if we need to add functionality to an existing method, rather than simply adding a bunch of lines of code and risk violating one or more SOFA guidelines, we can apply Extract Method to place the functionality in a new method that we call from the existing method. As you can see, this technique has the nice benefit that we already know how to develop new methods using TDD!

This observation explains why TDD leads naturally to good and testable code—it’s hard for a method not to be testable if the test is written first—and illustrates the rationale behind the “refactor” step of Red–Green–Refactor. If you are refactoring constantly as you code, each individual change is likely to be small and minimally intrusive on your time and concentration, and your code will tend to be beautiful. When you extract smaller methods from larger ones, you are identifying collaborators, describing the purpose of code by choosing good names, and inserting seams that help testability. When you rename a variable more descriptively, you are documenting design intent.

But if you continue to encrust your code with new functionality without refactoring as you go, when refactoring finally does become necessary (and it will), it will be more painful and require the kind of significant scaffolding described in Sections 9.2 and 9.3. In short, refactoring will suddenly change from a background activity that takes incremental extra time to a foreground activity that commands your focus and concentration at the expense of adding customer value.

Since programmers are optimists, we often think “That won’t happen to me; I wrote this code, so I know it well enough that refactoring won’t be so painful.” But in fact, your code becomes legacy code the moment it’s deployed and you move on to focusing on another part of the code. Unless you have a time-travel device and can talk to your former self, you might not be able to divine what you were thinking when you wrote the original code, so the code’s clarity must speak for itself.

This Agile view of continuous refactoring should not surprise you: just as with development, testing, or requirements gathering, refactoring is not a one-time “phase” but an ongoing process. In Chapter 12 we will see that the view of continuous vs. phased also holds for deployment and operations.

It may be a surprise that the fundamental characteristics of Agile make it an excellent match to the needs of software maintenance. In fact, we can think of Agile as not having a development phase at all, but being in maintenance mode from the very start of its lifecycle!

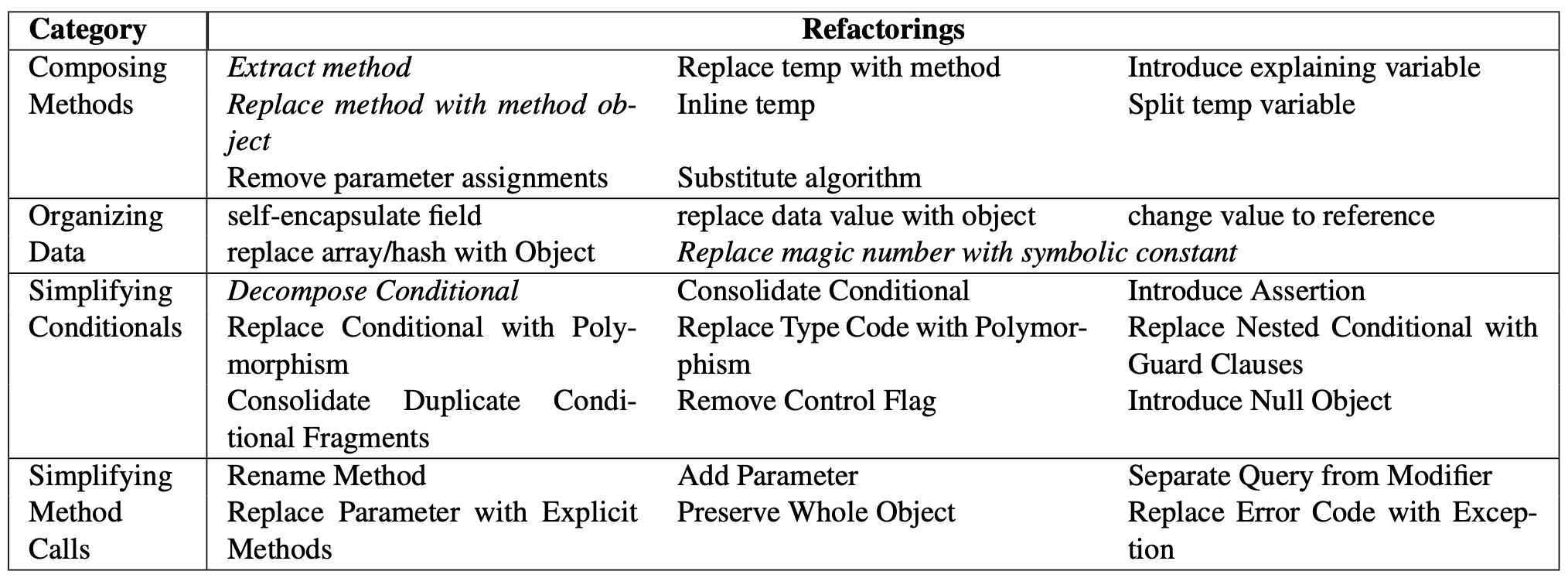

Working with legacy code isn’t exclusively about refactoring, but as we’ve seen, refactoring is a major part of the effort. The best way to get better at refactoring is to do it a lot. Initially, we recommend you browse through Fowler’s refactoring book just to get an overview of the many refactorings that have been cataloged. We recommend the Ruby-specific version (Fields et al. 2009), since not all smells or refactorings that arise in statically-typed languages occur in Ruby; versions are available for other popular languages, including Java. We introduced only a few in this chapter; Figure 9.22 lists more. As you become more experienced, you’ll recognize refactoring opportunities without consulting the catalog each time.

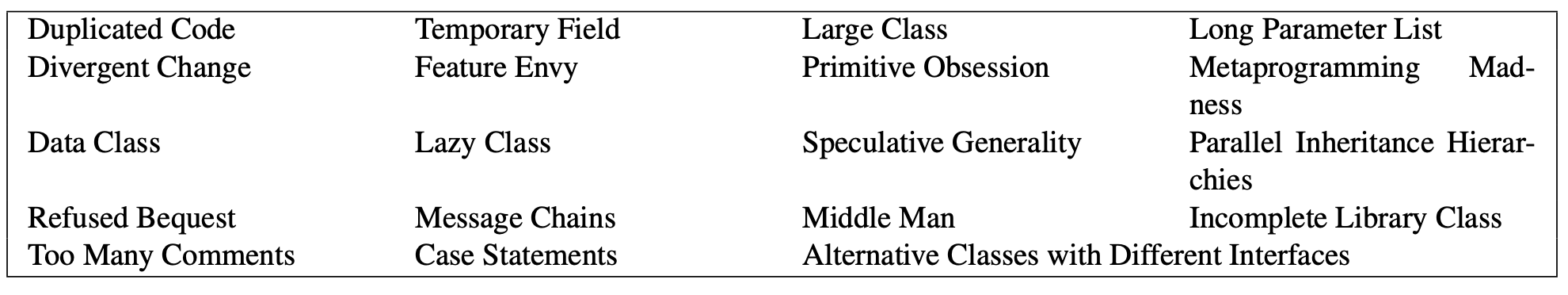

Code smells came out of the Agile movement. Again, we introduced only a few from a more extensive catalog; Figure 9.23 lists more. Good programmers don’t deliberately create code with code smells; more often, the smells creep in as the code grows and evolves over time, sometimes beyond its original design. Pytel and Saleh’s Rails Antipatterns (Pytel and Saleh 2010) and Tucker’s treatment of code smells and refactoring in the context of contributing 2011) to open source software (Tucker et al. 2011) address these realistic situations.

We also introduced some simple software metrics; over four decades of software engineering, many others have been produced to capture code quality, and many analytical and empirical studies have been done on the costs and benefits of software maintenance. Robert Glass (Glass 2002) has produced a pithy collection of Facts & Fallacies of Software Engineering, informed by both experience and the scholarly literature and focusing in particular on the perceived vs. actual costs and benefits of maintenance activities.

Sandi Metz’s Practical Object-Oriented Design in Ruby Metz 2012 covers object-oriented design from the perspective of minimizing the cost of change, and expands on many of the themes in this chapter with practical examples.

The other primary sources for this chapter are Feathers’s excellent practical treatment of working with legacy code (Feathers 2004), Nierstrasz and Demeyer’s book on reengineering object-oriented software (Nierstrasz et al. 2009), and of course, the Ruby edition of Fowler’s classic catalog of refactorings (Fields et al. 2009).

Finally, John Ousterhout’s A Philosophy of Software Design Ousterhout 2018 contains lots more practical advice for structuring software at the class and method level, with a view towards robustness and manageability. It’s aimed at more advanced developers and is an excellent source of wisdom when you’re ready to go beyond the introductory material in this chapter.