11.10. Concluding Remarks: Frameworks Capture Design Patterns¶

The process of preparing programs for a digital computer is especially attractive, not only because it can be economically and scientifically rewarding, but also because it can be an aesthetic experience much like composing poetry or music.

—Donald Knuth

The idea of design patterns is inspired by Christopher Alexander’s 1977 book A Pattern Language: Towns, Buildings, Construction describing design patterns for civil architecture. Erich Gamma, Richard Helm, Ralph Johnson and John Vlissides (the “Gang Of Four” or GOF) published the seminal book Design Patterns: Elements of Reusable Object-Oriented Software in 1995 (Gamma et al. 1994). It described what are now called the 23 GOF Design Patterns focusing on class-level structures and behaviors. The original 23 design patterns from the Gang of Four have been expanded dramatically since their book appeared. There are numerous repositories of design patterns (Cunningham 2013; Noble and Johnson 2013), with some tailored to specific problem areas such as user interfaces (Griffiths 2013; Toxboe 2013).

Despite design patterns’ popularity as a tool, they have been the subject of some critique; for example, Peter Norvig, currently Google’s Director of Research, has argued that some design patterns just compensate for deficiencies in statically-typed programming languages such as C++ and Java, and that the need for them disappears in dynamic languages such as Lisp or Ruby. Notwithstanding some controversy, patterns of many kinds remain a valuable way for software engineers to identify structure in their work and bring proven solutions to bear on recurring problems.

A problem for novice developers is that even if you read the Gang of Four book or study these repositories, it is hard to know which pattern to apply. If you don’t have previous experience with a given design pattern, and you try to design for it in an anticipatory manner, you’re more likely to get it wrong, so you should instead wait to add it later when and if it’s really needed.

The good news is that frameworks like Rails encapsulate others’ design experience to provide abstractions and design constraints that have been proven through reuse. For example, it may not occur to you to design your app’s actions around REST, but it turns out that doing so results in a design that is more consistent with the scalability success stories of the Web. While the Gang of Four went out of their way to differentiate design patterns from frameworks to try to make it clear what design patterns are—more abstract, narrower in focus, and not targeted to a problem domain—today frameworks are a great way for a novice to get started with design patterns. By examining the patterns in a framework that are instantiated as code, you can gain experience on how to create your own code based on design patterns.

Design Patterns (Gamma et al. 1994) is the classic Gang of Four text on design patterns. While canonical, it’s a bit slower reading than some other sources, and the examples are heavily oriented to C++. Design Patterns in Ruby (Olsen 2007) treats a subset of the GoF patterns in detail showing Ruby examples. It also discusses patterns made unnecessary by Ruby language features. Clean Code (Martin 2008) has a more thorough exposition of both the SOFA and SOLID guidelines that motivate the use of design patterns.

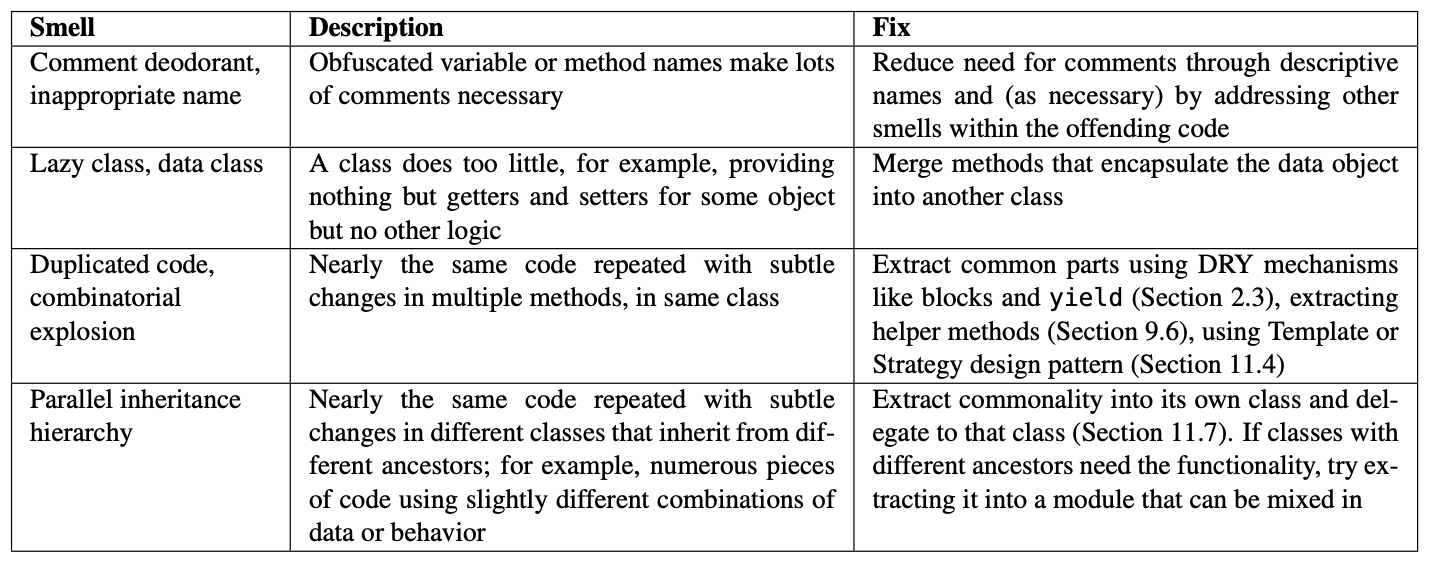

Rather than presenting a “laundry list” of patterns, we tried to motivate a subset of patterns by showing the design smells they fix. Rails Antipatterns (Pytel and Saleh 2010) gives great examples of how real-life code that starts with a good design can become cluttered over time, and how to beautify and streamline it by refactoring, often using one or more of the appropriate design patterns. Figure 11.24 shows a few examples of those refactorings, largely drawn from Martin Fowler’s online catalog of refactorings and comprehensive book (Fields et al. 2009).

Finally, M.V. Mäntyllä and C. Lassenius have created an online taxonomy of code and design smells grouped into descriptively-named categories such as “The Bloaters”, “The Change Preventers”, and so on, summarizing their 2006 journal article16 on this topic.