6.8. Testing Java Script and AJAX¶

Even our simple AJAX example has many moving parts. In this section we show how to test it using Jasmine, an open-source JavaScript TDD framework developed by Pivotal Labs. Jasmine is designed to mimic RSpec and support the same TDD practices RSpec supports. The rest of this section assumes you’ve read Chapter 8 or are otherwise proficient with TDD and RSpec; as Figure 6.16 shows, we will reuse all those TDD concepts in Jasmine.

To start using Jasmine, add the jasmine-rails and jasmine-jquery-rails gems to the development and test

groups in your Gemfile,and run bundle as usual, then run the commands in Figure 6.17 from your app’s root

directory. Create a simple example spec file spec/javascripts/basic_check_spec.js containing the following code:

rails generate jasmine_rails:install

mkdir spec/javascripts/fixtures

git add spec/javascripts

describe('Jasmine basic check', function() {

it('works', function() { expect(true).toBe(true); });

});

To run Jasmine tests, just start your app as usual with the rails server command, and once it’s running, browse

to the specs subdirectory of your app (so, for example, https://workspace–username.c9users.io/specs if running on

Cloud9, or http://localhost:3000/specs if developing on your own computer) to run all the specs and see the results.

From now on, when you change any code in app/assets/javascripts or tests in spec/javascripts, just reload the browser

page to rerun all the tests.

Testing AJAX code must address two problems, and if you have read about TDD in Chap- ter 8, you’re already familiar with the solutions to both. First, just as we did in Section 8.4, we must be able to “stub out the Internet” by intercepting AJAX calls, so that we can return “canned” AJAX responses and test our JavaScript code in isolation from the server. We will solve this problem using stubs. Second, our JavaScript code expects to find certain elements on the rendered page, but as we just saw, when running Jasmine tests the browser is viewing the Jasmine reporting page rather than our app. Happily, we can use fixtures to test JavaScript code that relies on the presence of certain DOM elements on the page, just as we used them in Section 8.6 to test Rails app code that relies on the presence of certain items in the database.

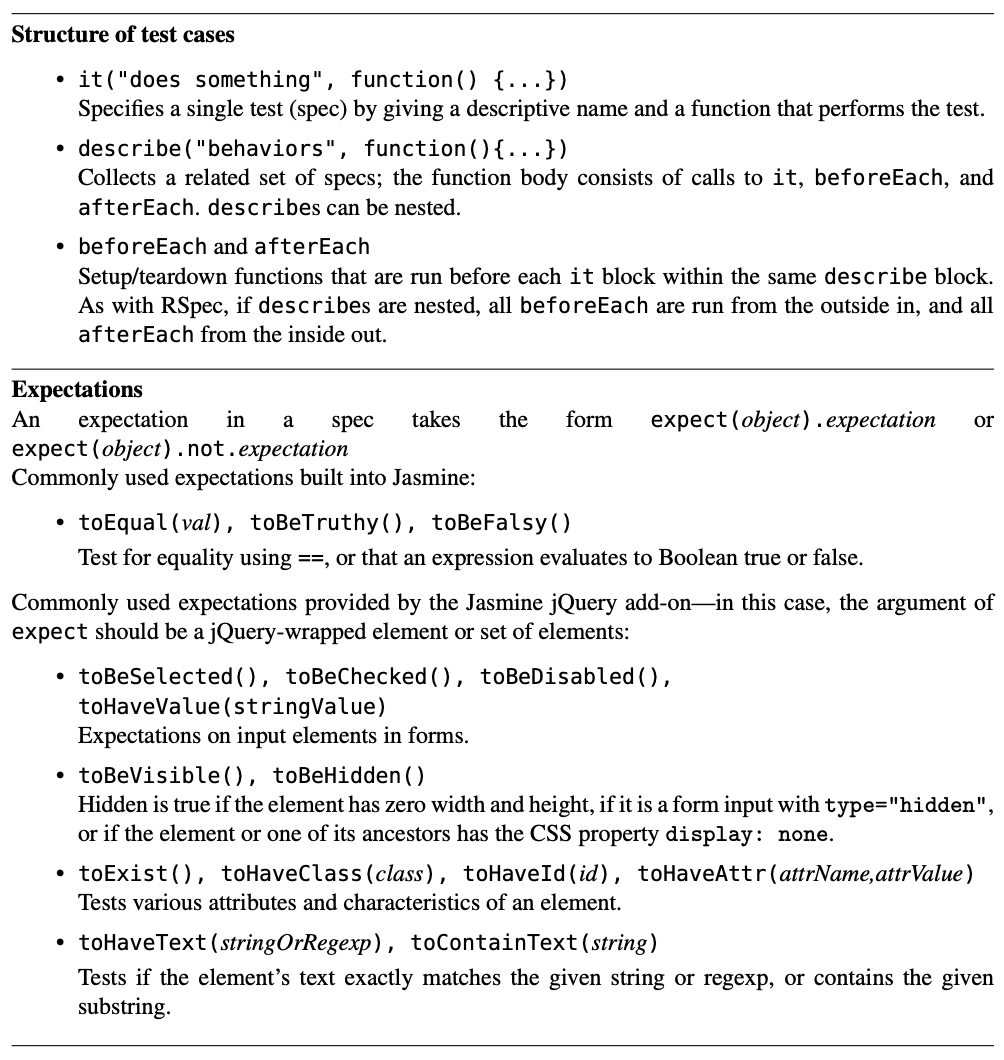

Figure 6.18 gives an overview of Jasmine for RSpec users. We will walk through five happy-path Jasmine specs for the popup-window functionality developed in Section 6.7. While these tests are hardly exhaustive even for the happy path, our goal is to illustrate Jasmine testing techniques generally and the use of Jasmine stubs and fixtures in AJAX testing specifically.

The basic structure of Jasmine test cases is immediately evident in Figure 6.20: like RSpec, Jasmine uses it to specify

a single example and nestable describe blocks to group related sets of examples. Just as in RSpec, describe and it take

a block of code as an argument, but whereas in Ruby code blocks are delimited by do...end, in JavaScript they are

anonymous functions (functions without a name) of zero arguments. The punctuation sequence }); is so prevalent because

describe and it are JavaScript functions of two arguments, the second of which is a function of no arguments.

The describe(’setup’) examples check that the MoviePopup.setup function correctly creates the #movieInfo container but

keeps it hidden from display. toExist and toBeHidden are expectation matchers provided by the Jasmine-jQuery add-on.

Since Jasmine loads all your JavaScript files before running any examples, the call to setup (line 34 of Figure 6.14)

occurs before our tests run; hence it’s reasonable to test whether that function did its work.

1describe('MoviePopup', function() {

2 describe('setup', function() {

3 it('adds popup Div to main page', function() {

4 expect($('#movieInfo')).toExist();

5 });

6 it('hides the popup Div', function() {

7 expect($('#movieInfo')).toBeHidden();

8 });

9 });

10 describe('clicking on movie link', function() {

11 beforeEach(function() { loadFixtures('movie_row.html'); });

12 it('calls correct URL', function() {

13 spyOn($, 'ajax');

14 $('#movies a').trigger('click');

15 expect($.ajax.calls.mostRecent().args[0]['url']).toEqual('/movies/1');

16 });

17 describe('when successful server call', function() {

18 beforeEach(function() {

19 let htmlResponse = readFixtures('movie_info.html');

20 spyOn($, 'ajax').and.callFake(function(ajaxArgs) {

21 ajaxArgs.success(htmlResponse, '200');

22 });

23 $('#movies a').trigger('click');

24 });

25 it('makes #movieInfo visible', function() {

26 expect($('#movieInfo')).toBeVisible();

27 });

28 it('places movie title in #movieInfo', function() {

29 expect($('#movieInfo').text()).toContain('Casablanca');

30 });

31 });

32 });

33});

<div id="movies">

<div class="row">

<div class="col-8"><a href="/movies/1">Casablanca</a></div>

<div class="col-2">PG</div>

<div class="col-2">1943-01-23</div>

</div>

</div>

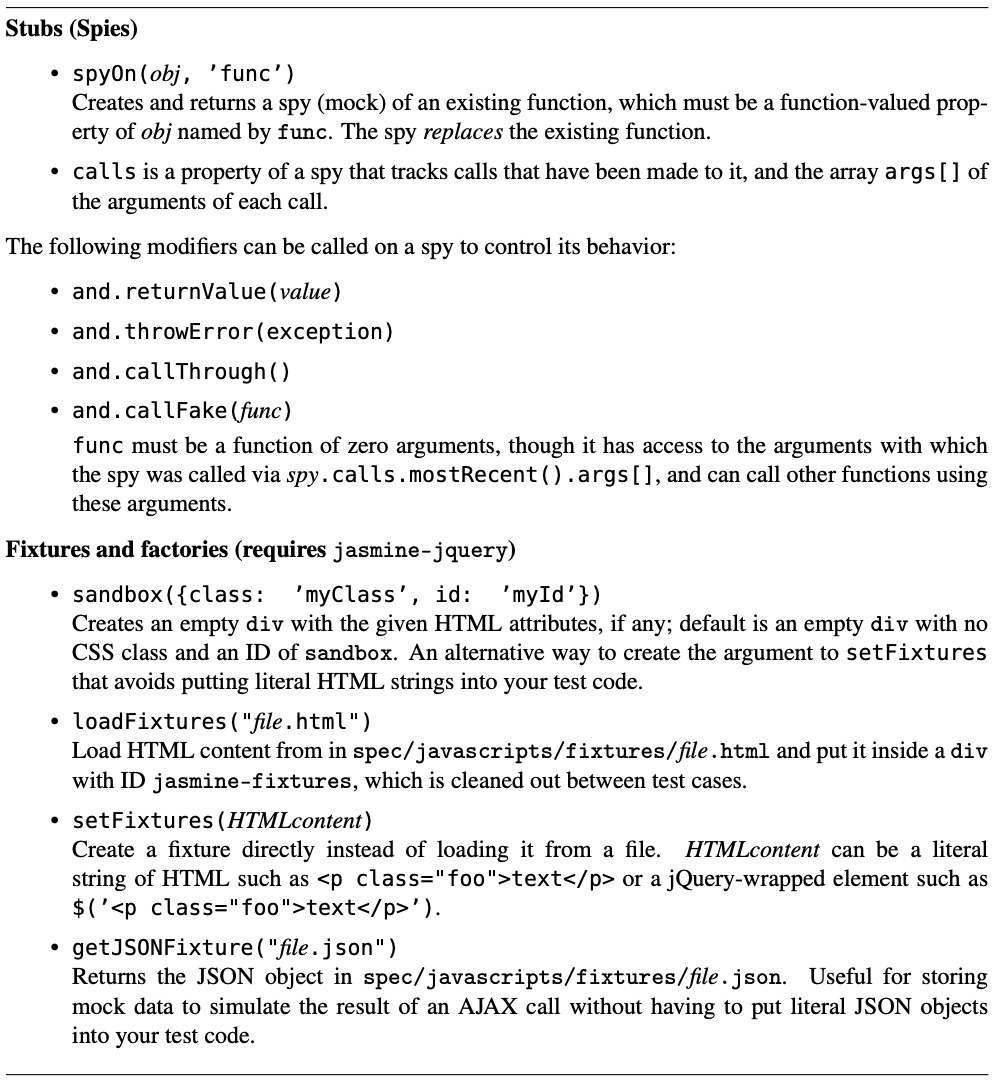

The describe( ’AJAX call to server’ ) examples are more interesting because they use stubs and fixtures to isolate our

client-side AJAX code from the server with which

it communicates. Figure 6.19 summarizes the stubs and fixtures available in Jasmine and Jasmine-jQuery. Like RSpec, Jasmine

allows us to run test setup and teardown code using beforeEach and afterEach. In this set of examples, our setup code loads

the HTML fixture shown in Figure 6.21, to mimic the environment the getMovieInfo handler would see if it was called after

movie list was displayed. The fixtures functionality is provided by Jasmine-jQuery; each fixture is loaded inside of

div#jasmine-fixtures, which is inside of div#jasmine_content on the main Jasmine page, and all the fixtures are cleared out

after each spec to preserve test independence.

The first example (line 12 of Figure 6.20) checks that the AJAX call uses the correct movie URL derived from the table.

To do this, it uses Jasmine’s spyOn to stub out the $.ajax function. Like RSpec’s stub, this call replaces any existing

function of the same name, so when we manually trigger the click action on the (only) a element in the #movies table,

if all is working well we should expect our spy function to have been called. Because in JavaScript it’s common for

functions to be the values of object properties, spyOn takes two arguments, an object ($) and the name of the function-valued

property of that object on which to spy (’ajax’).

Line 15 looks complex, but it’s straightforward. Each Jasmine spy remembers the argu- ments passed to it in each of its

calls, e.g. calls.mostRecent(), and as you recall from the explanation in Section 6.7, a real call to the AJAX function

takes a single object (lines 9–15 of Figure 6.14) whose url property is the URL to which the AJAX call should go. Line 15

of the spec is simply checking the value of this URL. In effect, it’s testing whether $(this).attr(’href’) is the correct

JavaScript code to extract the AJAX URL from the table.

Figure 6.22 shows the similarity between the challenges of stubbing the Internet for testing AJAX and stubbing the Internet for testing code in a Service-Oriented Architecture (Section 8.4). As you can see, in both scenarios, the decision of where to stub depends on how much of the stack we want to exercise in our tests.

<p>Casablanca is a classic and iconic film starring

Humphrey Bogart and Ingrid Bergman.</p>

<a href="" id="closeLink">Close </a>

describe('element sanitizer', function() {

it('removes IMG tags from evil HTML', function() {

setFixtures(sandbox({class: 'myTestClass'}));

$('.myTestClass').text("Evil HTML! <img src='http://evil.com/xss'>");

$('.myTestClass').sanitize();

expect($('.myTestClass').text()).not.toContain('<img');

});

});

Line 19 reads in a fixture that will take the place of the ajax response from the movies controller show action,

see Figure 6.23. In lines 20–22 we see the use fo the callFake function to not only intercept an AJAX call, but

also to fake a successful response using the fixture. This and the triggering of the AJAX call (line 23) is repeated

for each of the following two tests which check that both the #movieInfo popup is visible (line 26) and that it

contains text from the movie description (line 29).

This concise introduction, along with the summary tables in this section, should get you started using BDD for your JavaScript code. The best sources of complete documentation for these tools are the Jasmine documentation and the Jasmine jQuery add-on documentation.

Self-Check 6.8.1. Jasmine-jQuery also supports toContain and toContainText to check if a string of text or HTML

occurs within an element. In line 7 of Figure 6.20, why would it be incorrect to substitute .not.toContain(’<div id="movieInfo"></div>’) for

toBeHidden() ?

A hidden element is not visible, but it still contains the text or HTML associated with the element. Hence

toContain-style matchers can be used to test the content of an element but not its visibility. In addition, there are many ways for an element to be hidden—its CSS could includedisplay:none, it could have zero width and height, or its ancestor could be hidden—and thetoBeHidden()matcher checks all of these.

Self-Check 6.8.2. Like RSpec, Jasmine supports and.returnValue() for returning a canned value from a stub. In Figure 6.20,

why why did we have to write and.callFake to pass ajaxArgs to a function as the result of stubbing ajax, rather than simply

writing and.returnValue(ajaxArgs) ?

Remember that AJAX calls are asynchronous. It’s not the case that the

$.ajaxcall returns data from the server: normally, it returns immediately, and sometime later, your callback is called with the data from from the server.and.callFakesimulates this behavior.